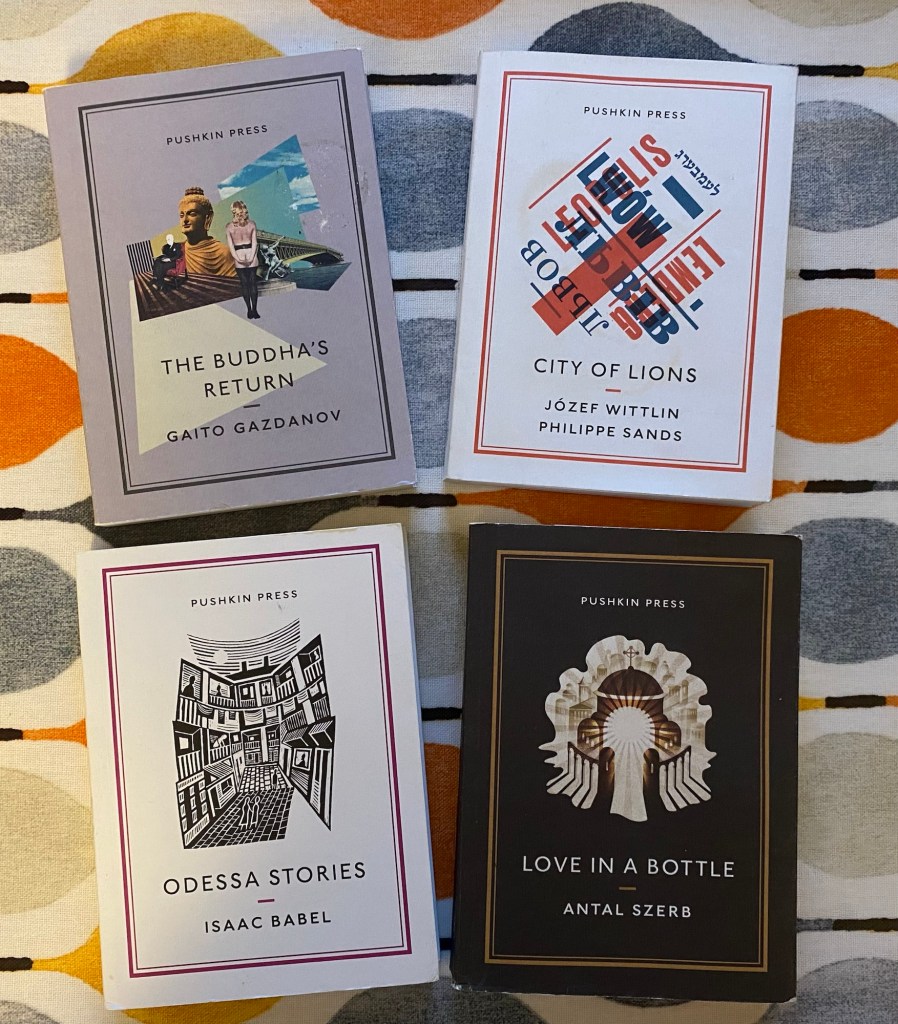

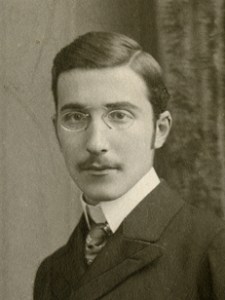

This week I’m focussing on Pushkin Press as part of Kaggsy and Lizzy’s #ReadIndies event to finally read four books that have long been in the TBR. For this third post today my read is Odessa Stories by Isaac Babel (1916-1937 transl. Boris Dralyuk 2016).

The Introduction to this volume by translator Boris Dralyuk is really informative and provides some fascinating context to Babel’s writing. Odessa was a booming port when Babel was born in 1894; in 1900 around 140,000 of its 400,000 population was Jewish. Babel was part of a well-to-do family but was drawn to Odessa’s underbelly, writing stories about the legendary gangsters of the city.

Dralyuk also explains about translating the melting-pot language of Odessa, so I highly recommend reading the Introduction before you start on the stories (I often read Introductions at the end). Babel was only 45 when he was killed in Stalin’s purges.

The volume is divided into three parts: Gangsters and Other Old Odessans; Childhood and Youth; and Love Letters and Apocrypha. I always struggle to write about short story collections and generally Babel’s stories are so short that I don’t want to give spoilers. Here I just want to give a flavour and you can see if you might want to seek out these stunning stories for yourself.

The first part is mainly told in the third person and weaves together tales of violence and corruption, with recurring characters including “Benya Krik, gangster and King of the gangsters”. The tales are colourful and carnivalesque, but Babel never allows the broader strokes to obscure the unlawful methods that so many live by:

“At this wedding they served turkey, roast chicken, goose, gefilte fish and fish soup in which lakes of lemon glimmered like mother-of-pearl. Flowers swayed above the dead goose heads like lush plumage. Does the foamy surf of Odessa’s sea wash roast chickens ashore?”

At the same time, he doesn’t position the reader above the gangsters or way of life. Babel suggests that this side of Odessa is as it is because this the logical way to be, and it has emerged as part of the society, laws and political structures that surround it:

“Let’s not throw dust in each other’s eyes. There’s no one else in the world like Benya the King. He cuts through lies and looks for justice, be it justice in quotes or without them. While everyone else, they’re as calm as clams. They can’t be bothered with justice, won’t go looking for it – and that’s worse.”

The second part of the stories in Childhood and Youth becomes more personal, with first-person tales that follow on from one another in some instances. I understand The Story of My Dovecote is the most famous, and rightly so. Within this brilliant collection, it still stands out. (Skip the next two paragraphs if you don’t want to know any details in advance.)

A young boy has spent five of his ten years coveting a dovecote. He manages to find ways around the anti-Semitism at his school to do well academically and get the reward of finally being able to buy his doves. He sets out to the market with his money and gets his beloved birds, tucking them into his jacket. If your heart is sinking at this description, you are absolutely right…

The story is fifteen pages in this edition and completely devastating. I would urge anyone to read it, but it will absolutely stay with you. It will rip your heart out and stamp all over it. The final word of this story is “pogrom”.

There are lighter stories in this section too, such as The Awakening, about a precocious young man:

“Writing was a hereditary occupation in our family. Levi Yitzchak, who went mad in his old age, had spent his whole life composing a tale titled A Man With No Head. I took after him.”

Odessa Stories was my first experience of reading Babel and I was blown away. Babel clearly enjoyed the almost fabulist tales of Benya the King, but somehow never glamorised him. His writing is hugely entertaining but also truthful – the violence towards people and animals suddenly appears in the midst of the stories and jolts the reader to remember the visceral realities of what is being described.

In evoking the worst of human behaviour in Dovecote, Babel is restrained and absolutely drives home the tragedy.

Babel’s writing is intensely human, marrying together humour, violence, pathos and beauty seamlessly. I will definitely seek out more by him on the strength of Odessa Stories. Sadly, there isn’t much as his life was cut short. However, Pushkin Press publish Red Cavalry, another short story collection.

“For the first time I saw my surroundings as they actually were – hushed and unspeakably beautiful.”