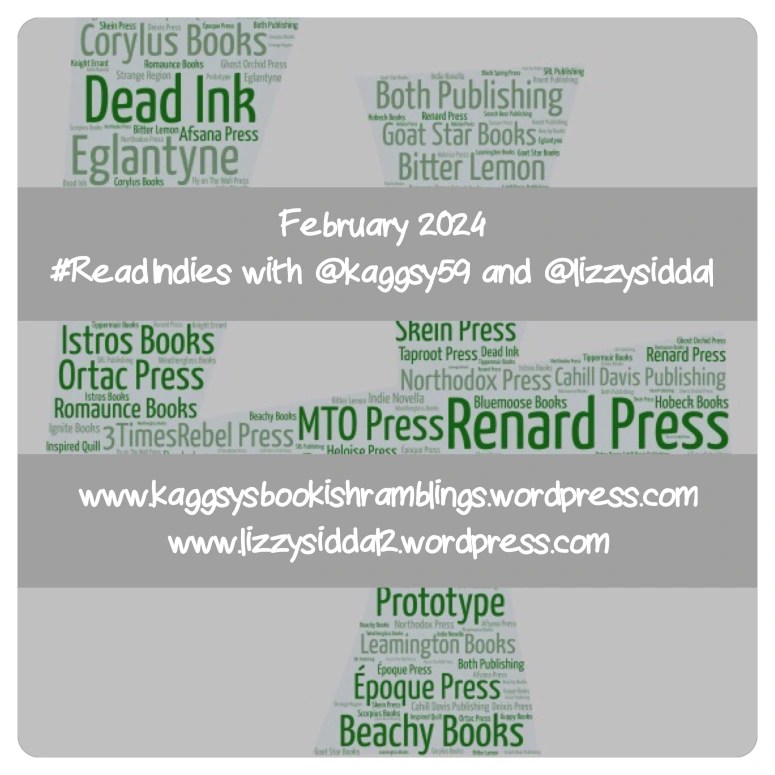

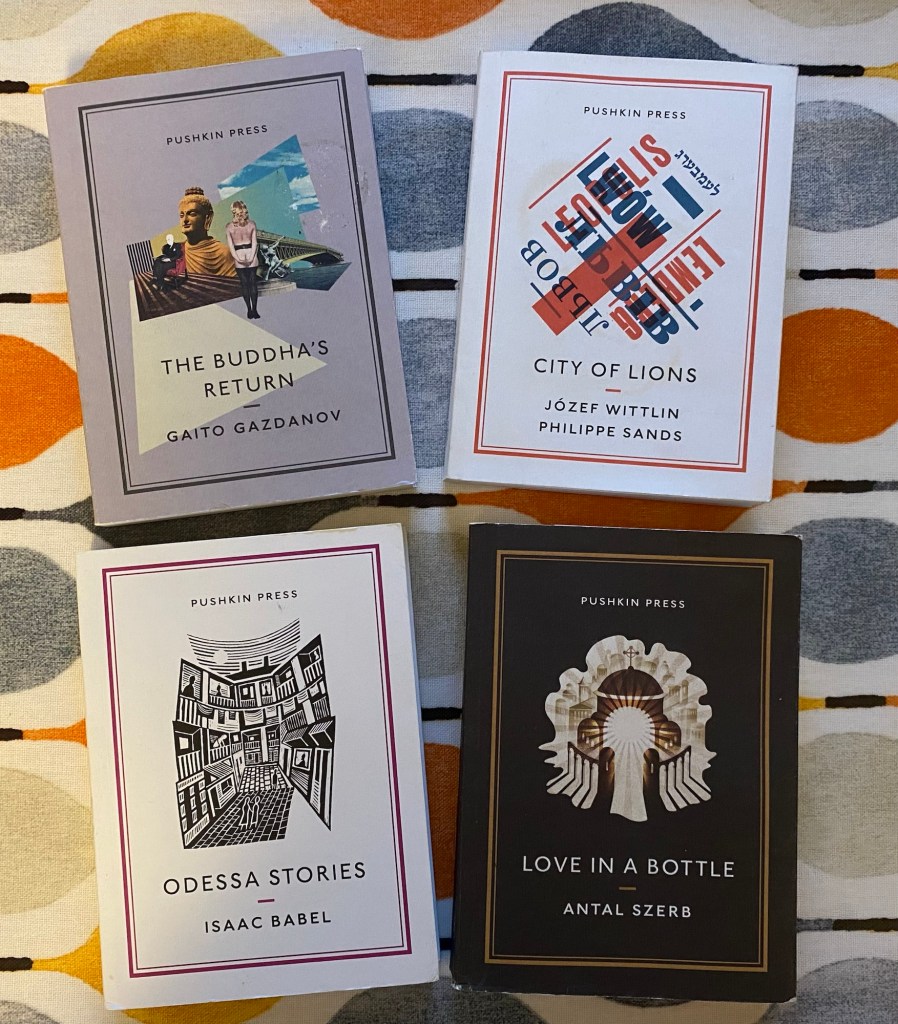

This month I started off my reading for Kaggsy and Lizzy’s #ReadIndies event with an author that the event had led me to discover last year: Gertrude Trevelyan. So it seemed apt to end this month’s reading with another author #ReadIndies had introduced me to last year: Antal Szerb. In 2024 reading Love in Bottle in February led to Journey by Moonlight for the 1937 Club in April. This time I’m looking at The Pendragon Legend (1934, transl. Len Rix 2006) which is published by the always reliable Pushkin Press.

The Pendragon Legend is Szerb’s first novel, and utterly bonkers. As I was reading it I remembered why I had enjoyed my previous Szerb reads so much: his wit, fun, intelligence without superiority, gentle ribbing without malice, make him such a joy.

The narrator Janos Bátky is a young scholar who spends his time hanging around the British Library Reading Room. Luckily for him, he has no need for money:

“My nature is to spend years amassing the material for a great work and, when everything is at last ready, I lock it away in a desk drawer and start something new.”

His current interest is Rosicrucians: “Nothing interests me more than the way people relate emotionally to the abstract.” This ancient secretive organisation’s interests include: “Changing base metals into gold, deliberately prolonging the life of the body, the ability to see things at a distance, and a kabbalistic system for solving all mysteries.”

This leads to him being introduced to the Earl of Gwynedd who invites Janos to stay at Pendragon Castle and make use of his library. Janos heads off to Wales with some acquaintances in tow, unheeding the warnings of a mysterious telephone call… (why do people never heed mysterious telephonic warnings??)

Shortly into his stay there are both earthly concerns when bullets are stolen from his gun and metaphysical concerns where he seems to be haunted:

“Just to be clear on this: not for a moment did I think it could be any sort of ghostly apparition. While it is a fact that English castles are swarming with ghosts, they are visible only to natives – certainly not to anyone from Budapest.”

(This isn’t the only time Janos confuses England and Wales, despite the fact he encounters similar ignorance when people insist he must be German and that Hungary doesn’t exist: “’Come off it. Those places were made up by Shakespeare.’”)

There are femme fatales, reluctant heroes, knowing castle staff… my favourite character was the capable and blunt Lene Kretsch:

“This was how our friendship began: I set myself on fire and she put me out. I’d been sitting by the hearth with The Times. I’ve never been able to handle English newspapers – apparently one has to be born with the knack of folding these productions into the microscopic dimensions achieved by the natives – and, as I flicked a page over, the entire room filled with newsprint.”

And so The Pendragon Legend is a mystery, a thriller, a Gothic ghost story, a fable, and with the arrival of the Earl’s niece Cynthia, a romance, despite Janos’ callowness:

“I can never feel much attraction to a woman whom I consider clever – it feels too much like courting a man.”

Maybe Cynthia has more tolerance for him as she comes from a family where: “At most, the Pendragons tolerate women within the limits of marriage, and even then without much enthusiasm.”

Szerb satirises romance along with all the other tropes and genres he employs, but always with affection and never with any disdain. Somehow Janos and assorted friends bumble their way through the mystery, despite the poisonings, blackmail and hauntings which dog their steps.

My one reservation is that it became a bit too esoteric towards the end, but this is a matter of personal taste and feels a bit mean-spirited in the face of such an affectionate and fun tale.

If you fancy a pacy, ridiculous, learned adventure, The Pendragon Legend is for you.

“I was filled with the tenderness I always feel – and which nothing can match – when I encounter so many books together. At moments like these I long to wallow, to bathe in them, to savour their wonderful, dusty, old-book odours, to inhale them through my very pores.”