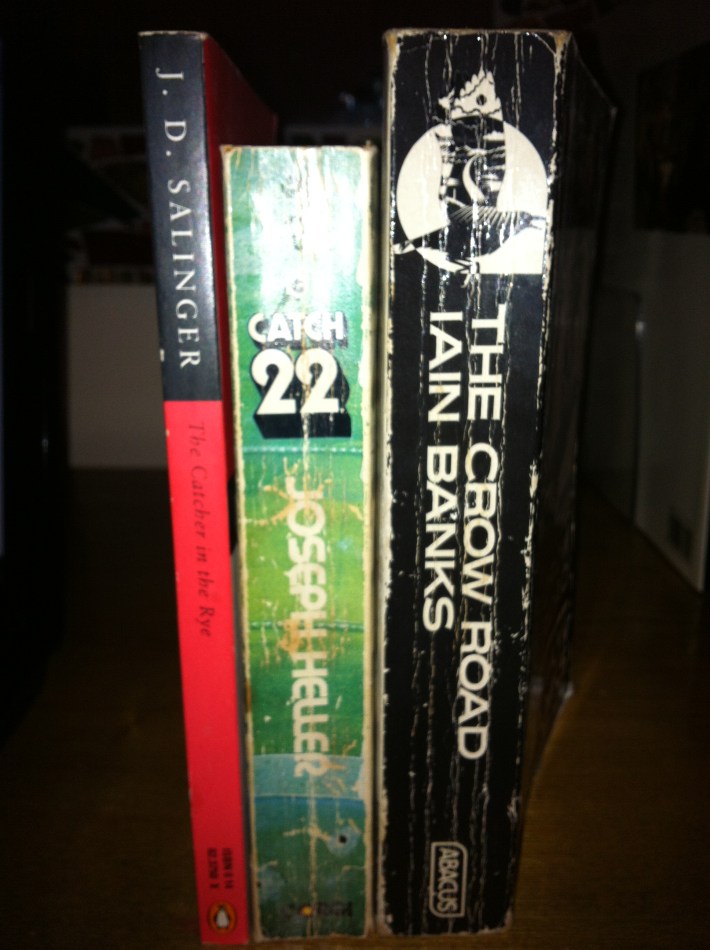

Before I start this post proper, I just wanted to mention the sad news that Iain Banks announced this week that he has terminal cancer. In almost 30 years Iain Banks has produced an impressive volume of work, including science fiction under the name Iain M. Banks, and aged only 59, it was reasonable to assume he would continue to do so for a great many years. Instead, he has confirmed that his latest novel, The Quarry, will be his last. I discuss my favourite of his novels, The Crow Road, in my post of 25 February. I really don’t know what else to say about this that won’t sound trite or clichéd, but I would urge you once more to check out the work of this highly readable writer whose talent will be sorely missed by his many fans worldwide.

***

The prompt for this post came from a friend who emailed this week asking me for recommendations of classics to read. She had just bought a Kindle and discovered the joy of copyright-free books being free to download. (All hail Project Gutenberg). So I thought lots of people could be in a similar position, and it would make a good post… how wrong I was. It wasn’t long into my deliberations (which I’d love to claim involves a complicated algorithm I’ve compiled to ensure the most riveting blog possible, but the reality is me staring mindlessly at my bookshelves and shaking my head whilst eating too much chocolate) that I ran into the truth of Alan Bennett’s definition. For so many of the books charged as classics I found myself asking – who needs me to recommend them? Everyone’s heard of them, knows what they’re about, has an idea of whether it’s something they’re interested in. OK, I don’t pick the world’s most obscure books the rest of the time, but classics don’t exactly need the PR. Then I decided to just chill out and pick a book each from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries that are classics but maybe not the most well-known ones. You’ll be relieved to know I scrapped that idea as I realised this would mean the post would go on forever, and like so many Modernists before me, I decided to abandon all thoughts of the nineteenth century. So here are two books, both of which you’ve probably heard of, one from the century that saw the birth of the novel, one from the twentieth century (unfortunately only the first one is free to download on Project Gutenberg). If you haven’t read them, I hope this post is helpful in adding to the belief that you have!

Firstly, The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling, by Henry Fielding (1749, my copy Penguin 1999). Written at the time when the novel as a form was just beginning, you can sense Fielding having a great time playing around with the lack of established rules – there a lots of direct addresses to the readers, often at tangents to the plot, including précis to each chapter such as “Chapter XII: containing what the Reader, may, perhaps, expect to find in it” and “Chapter I: containing little or nothing”. The book is a huge one: 346,747 words, according to Wikipedia, so I won’t attempt anything other than the very basic outline of the plot: Tom Jones is found abandoned in Squire Allworthy’s bed as a baby. The Squire raises him as a son, and Tom falls in love with his neighbour, the beautiful and virtuous (of course) Sophia. He has a nemesis, Bilfil (nephew to Squire Allworthy), whose machinations lead to Tom being banished from the house. He takes to the road, and Sophia, who loves him, runs away to find him. Adventures, trials and tribulations abound…

The Victorians reacted against the libertinism of the eighteenth century, but I think this liberal morality means the novels of the time are great fun. Tom Jones is picaresque, and as such Tom doesn’t always behave well, but it’s always believable and funny, and what makes it so endearing is that he really tries to be the hero of this novel. For example, when he hears the screams of a woman in a wood, he runs to her rescue. Except he half slides down a hill in a not-very-heroic manner, beats the man attacking her, and then rather than cover over the exposed woman, enjoys gazing at her breasts. The lady recovers sufficiently to flirt with him, and declines his offer of a coat:

“Thus our Heroe and the redeemed Lady walked in the same Manner as Orpheus and Eurydice marched heretofore. But tho’ I cannot believe that Jones was designedly tempted by his Fair One to look behind him, yet as she frequently wanted his Assistance to help her over Stiles, and had besides many Trips and other Accidents, he was often obliged to turn about.”

Needless to say, this being the eighteenth century, they end up acting on their inclinations…

Tom Jones is a classic that perhaps isn’t as well read as some of the novels that followed, their way opened by Fielding’s inventive work. I think that’s a shame. It’s funny, it has plenty to say, and although it’s satirical it’s not overly moral, so if you’ve been put off the classics by the heavily moral tone of the Victorians (or Fielding’s contemporary, Samuel Richardson) then Fielding could be the author for you. And although Tom Jones is long, it’s not nearly as long & impenetrable as other eighteenth century classics like Tristram Shandy and Clarissa. As a free download, you won’t even have to wrestle with an unwieldy paper tome, so there’s no reason to be anything other than content: “a blessing greater than riches; and he to whom that is given need ask no more.”

My second choice, Scoop by Evelyn Waugh, runs to a modest 222 pages in my edition (Penguin, 1938; my copy much later but no date given) so if you can’t face the girth of Tom Jones, maybe this will appeal more. Scoop is Waugh’s satire on the newspaper business, and the integrity (or lack thereof) of an industry looking for a story at any cost is thoroughly lampooned.

William Boot writes countryside columns for the Daily Beast. The newspaper’s owner, Lord Copper, mistakes him for the novelist John Boot, who wants to leave the country, and so sends him to be a war correspondent in Ishmaelia, a (fictional) country on the verge of civil war. The whole experience is disastrous for Boot, but he does manage a scoop, and so is proclaimed a wild success. The novel is full of Waugh’s witty turns of phrase (Boot is served at one point by a page “with a face of ageless evil”)and eccentric characters, who ask questions like: “Why should I go to Viola Chasm’s Distressed Area; did she come to my Model Madhouse?” If you enjoyed Vile Bodies, this style will be familiar to you, but here the humour is employed to expose the faults inherent in the Press rather than the Bright Young Things of the interwar years. Waugh is scathing about the process of news journalism as a whole: “News is what a chap who doesn’t care much about anything wants to read. And its only news until he’s read it. After that it’s dead.” The facts of the war are unimportant to the journalists, as Boot is instructed at one point: “From your point of view it will be quite simple. Lord Copper only wants Patriot victories and both sides call themselves patriots, and of course both sides will claim all the victories.”

I don’t know a lot about journalism today but I suspect Scoop hasn’t dated too badly, and therefore the satire stands up as well today as it ever did. One thing which doesn’t stand up & which I found shocking is the horrifically racist language used through the book. It’s not in abundance, but there’s enough of it there for me to feel the need to warn you. Ishmaelia is set in Africa, and the language used by the white journalists to describe the country’s inhabitants is derogatory and hugely offensive – it is probably also, I fear, an accurate portrayal of attitudes at the time. I would still recommend Scoop as a novel, but I wish I’d known about this facet of the story before I went in, as I would have felt better prepared to manage it.

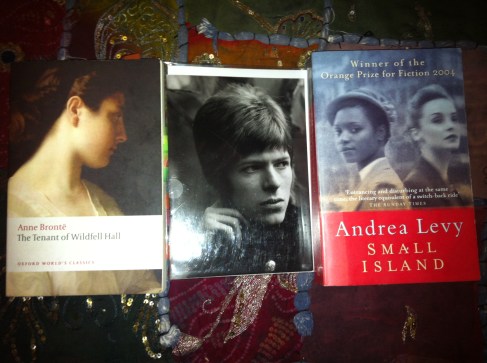

Here are the books presented in classical style, on a bookshelf!