The Guardian newspaper has a series it runs on Saturdays, called The Q&A, short interviews with celebrities. One of the regular questions is: “What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?” I don’t even have to pause for thought to answer this one. Having lived with myself all these years there are plenty of things I deplore in myself, but far and away is my enormous capacity for procrastination. Since I’ve started this blog, my procrastination has developed two-fold: I use the blog to procrastinate from whatever else I’m meant to be doing, and the blog also provides something else I procrastinate over. Let’s just say there’s some reading for next term not getting done right now, and certain members of my household facilitate my procrastination by indulging their favourite pastime of sitting on my laptop – how can I possibly work in these conditions?

If you are fellow procrastinator, take heart from the fact that you are in great company. Famous procrastinators include Leonardo da Vinci, Douglas Adams, Franz Kafka and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The last of these is who I turn to now, with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. You can read the full poem here. This famous long poem tells the story of a mariner cursed after he shoots an albatross that had brought a warm wind to his ship:

And I had done a hellish thing,

And it would work ’em woe:

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay,

That made the breeze to blow!

As a result of his actions, he has to wear the albatross around his neck (hence the phrase for a guilty burden) and the ship is taken into new waters by vengeful spirits where the crew begin to die.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death-fires danced at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

As these lines show, there is an eerie, hallucinatory quality to the imagery that really evokes a feeling of desolation and disquiet on a vast expanse of ocean. The atmosphere of the poem is deeply unsettling.

When the mariner begins to appreciate the natural life around him, he prays, and the albatross falls from his neck, lifting the curse.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water-snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessèd them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The self-same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

However, the Mariner is left to wander the earth, telling his story. It is not a comfortable resolution, and apparently Coleridge was in some sort of spiritual crisis when he wrote this poem. But although it’s an uncomfortable read, it’s also Coleridge at his best, and the imagery is beautiful and arresting. Definitely worth a read, and as a procrastination tool it should use up about an hour.

Secondly, back to the twenty-first century with Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple. Semple used to write for various television shows, including one of my all-time favourites, Arrested Development, so I approached this novel with high hopes. I wasn’t let down. The novel is funny, but not at the expense of the characters. Semple manages to create people you really care about, even as you laugh at their foibles and delusions. I chose it for this post because Bernadette is an architect who hasn’t created anything in years. The novel is told from the point of view of her adoring 15-year-old daughter Bee, but also multiple viewpoints as we read letters, emails, notes and even a transcript of a TED talk. Bernadette lives with her husband and daughter in a crumbling building:

“All day and night it cracks and groans, like it’s trying to get comfortable but can’t, which I’m sure has everything to do with the huge amount of water it absorbs any time it rains. It’s happened before that a door all of a sudden won’t open because the house has settled around it.”

“I knew our blackberry vines were buckling the library floor and causing weird lumps in the carpet and shattering basement windows. But I had a smile on my face, because while I slept, there was a force protecting me.”

Bernadette hates living in Seattle, “this Canada-close sinkhole they call the Emerald city”. She responds with antagonism bordering on aggression to the parents at Bee’s school who try and get her involved in the “community”. Then one day she disappears. As Bee tries to put together what’s happened and find her idiosyncratic, forceful mother, the various characters emerge through Bee’s impression of them and their own words in the various transcripts that make up the novel. They are all flawed, funny, recognisable and likeable. Even the character I most wanted to throttle redeemed herself in the end.

Although it’s Bee looking for her mother, the title is Where’d You Go, Bernadette, not Where’d You Go, Mom. Ultimately the novel is about Bernadette’s search for herself, because, as a friend of hers points out: “If you don’t create, Bernadette, you will become a menace to society”. And funny though Bernadette’s menace is, you’re rooting for this eccentric and engaging character to find her way back to working again. Where’d You Go, Bernadette is a reassuring, feel-good novel about how we’re all trying to get through life and not lose ourselves along the way.

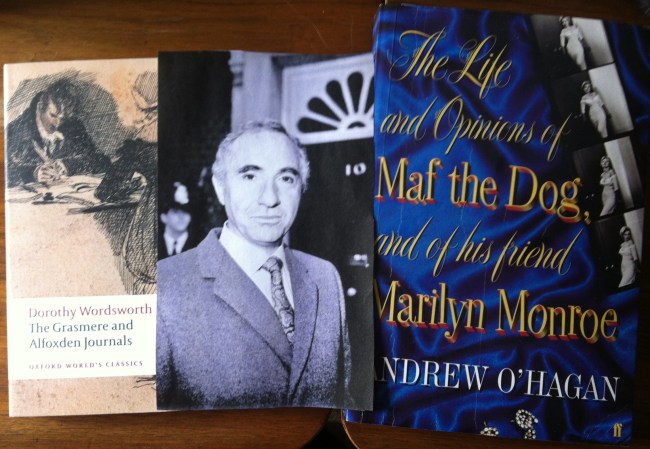

Normally I end with a photo of the books, but I thought it was apt to the theme of procrastination not to get round to it. Instead here is Tim from The Office exploring his favourite way to procrastinate, by torturing Gareth: