This is my contribution to Dean Street December, a month-long celebration of this wonderful indie publisher, hosted by Liz at Adventures in Reading, Running and Working from Home.

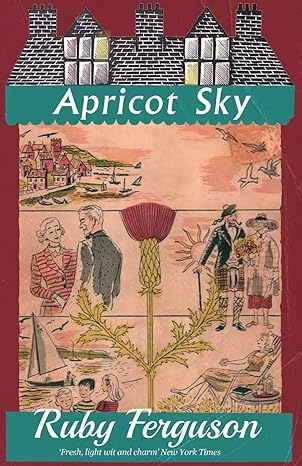

Dean Street Press’ imprint Furrowed Middlebrow focuses on early and mid-twentieth century women writers, and it’s from this collection that I’ve chosen my read, Apricot Sky by Ruby Ferguson (1952 – please note for Simon and Kaggsy’s 1952 Club running next year!)

I must confess that rather than a DSP edition, my copy is a nice little hardback I found in my local charity shop, inscribed with the author’s love to Flossie and John 😊 I picked up her later novel The Leopard’s Coast at the same time, also given with the author’s love, so I wonder if Flossie and John lived near me and their books have been cleared out…?

Aside from the Jill pony books I read as a child, I only knew Ruby Ferguson from Lady Rose and Mrs Memmary (1937) republished by Persephone Books. But I’d enjoyed that so much that I felt confident enough to swoop up the two books when I saw them; and what a total joy Apricot Sky turned out to be.

Set in 1948 in the Highlands of Scotland, the story follows the MacAlvey family through the events of one summer. A descriptive passage on the first page sets the tone:

“The charm of islands which changed their colour every few minutes, of lilac peaks smudged on the farthest horizon, of white-capped waves on windy days, of distant steamers chugging romantically on their ways, of little boats with faded brown sails scudding before the breeze, of sudden storms pouring fiercely across the terrific expanse of sky and water, of thousands of seabirds planing and diving, of floods of sunshine scattering millions of diamonds upon the rippling waves, all this made-up the view about which the MacAlvey’s visitors had so much to say while the MacAlvey’s themselves listened indulgently and with inward amusement.”

The MacAlvey’s are a nice family living a life not without trials but without any great drama, comfortably well-off and settled.

“Kilchro House was noted for its hospitality. It was a gay house where a gay family gave charming entertainment and never tried to descend into banality by prattling about themselves.”

The MacAlvey’s younger daughter Raine is due to marry Ian, brother of the Laird of Larrich. This is the thread which runs through the novel, as the wedding gathers apace for the September ceremony.

Raine’s older sister Cleo is back from three years in America, everyone expecting her much changed, but her heart stayed with her Highland home, and Neil, the Laird. Whenever she sees him she becomes utterly tongue-tied, and feels entirely inadequate alongside the charms of Inga Duthie, a sophisticated widow who is new to the area.

“Cleo MacAlvey could think of no worse desolation than that those she liked should not like her. She was a great deal more diffident than her sister Raine, who barged through life without caring whether people liked her or not, and was about as introverted as a fox-terrier puppy.”

Alongside these adult concerns are the younger children, left to their own devices. Primrose, Gavin, and Archie were orphaned by the war and live with their grandparents. The whole summer stretches before them:

“At Strogue there was no promenade and no cinema or skating-rink and only about three shops, and you couldn’t move without getting yourself in a mess with tar and fish and stuff left about, but everything you did there was full of exhilaration and had a way of turning out quite otherwise than you expected.”

They love boats and beaches and being out of doors. The only blight on their idyll is distant cousins Elinore and Cecil who come to stay for a few weeks. They are refined and self-contained, and in the case of Elinore, an unmitigated snob.

The children’s adventures are reminiscent of the Famous Five: there are islands, swimming and a big focus on picnics. There is post-war rationing to contend with, but it is seemingly straightforward to overcome – they frequently manage sweets, pies, jam, sandwiches and fizzy drinks.

For the adults, the trials are tedious houseguests in the shape of Dr and Mrs Leigh, and the appalling Trina, married to their son James. Mrs MacAlvey loves having guests though, and loves her family and her garden. Her part of the world gives her all she needs and she feels no desire to venture any further:

“She found herself unable to picture it, for she had never been to England, and always thought of it as being full of successful people living in Georgian houses.”

Despite being so rooted in her domestic life, she remains blissfully unaware of what her grandchildren get up to all day, and how tortured poor Cleo is by her unspoken love for Neil:

“Nobody talked about their feelings at Kilchro House, it was considered one stage worse than talking about your inside.”

I thoroughly enjoyed my summer with the MacAlvey family in a beautifully evoked part of the world, far away from chilly London. The stakes were soothingly low, and the humour was gentle. Any drama was short-lived, and things worked out exactly as they should.

If you are looking for a warm-hearted, escapist read, Apricot Sky will serve you well.

“‘All right,’ said Raine, holding out a ten-shilling note. ‘I’ll try anything once, even altering the course of history.’”