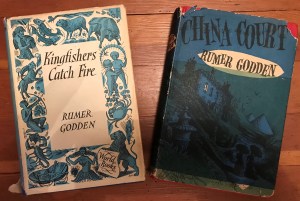

I would say my blogging this year has been a continual exercise in humility or humiliation, depending on my mood 😀 Once again, I have failed to realise my own expectations, this time that I would read The River (1946) and Breakfast with the Nikolides (1942) for Brona’s Rumer Godden Reading Week which ends today. I’ve really enjoyed the Rumer Godden novels I’ve read (The Greengage Summer, Black Narcissus, China Court, Kingfishers Catch Fire). Godden is a prolific author and I’ve barely scratched the surface so I was excited to see Brona’s event.

But sadly (predictably) yet again, I’ve ended up posting right up to the wire for a reading event. I’m just back from a weekend away in the New Forest with friends, and while I had a lovely time I got minimal reading done, so I’m not going to manage to squeeze in the second book. I have at least managed The River, which given that it’s only 111 pages cannot be taken as a sign my reading is recovering in any great way. Ah well…

In the preface to my edition, Godden describes how the novel was written following her passing-by her childhood home after many years, and the tone of the novella is elegiac, full of feeling for a time long past. It begins:

“The river was in Bengal, India, but for the purpose of this book, these thoughts, it might as easily have been a river in America, in Europe, in England, France, New Zealand … Its flavour would be different in each […]

That is what makes a family, the flavour, the family flavour, and no one outside the family, however loved and intimate, can share it.”

The family are a middle-class white family, living in India. Although told in third person, the point of view is that of Harriet, on the cusp of adolescence. Her family comprises her pregnant mother, father who runs a jute factory, older sister Bea and younger brother Bogey, toddler Victoria, and Nan.

Harriet is great character: strong-willed, stubborn, imaginative and inquisitive. She writes poems and it’s easy to assume that she is based on Godden. She’s struggling with changes in herself and her family. Bea is that bit older and drawing away from childhood, and therefore her younger siblings. Bogey is interested in local fauna and happy to be left to explore these alone. Harriet is left betwixt and between.

“ ‘You are always trying to stop things happening, Harriet, and you can’t.’

But Harriet still thought, privately, that she could.”

The short novel is full of gorgeous descriptions of India, from the bazaar:

“Harriet and the children knew the bazaar intimately; they knew the kite shop where they bought paper kites and sheets of thin exquisite bright paper; they knew the shops where a curious mixture was sold of Indian cigarettes and betel nut, pan, done up in leaf bundles, and coloured pyjama strings and soda water; they knew the grain shops and the spice shops and the sweet shops with their smell of cooking sugar and ghee, and the bangle shops, and the cloth shop where bolts of cloth showed inviting patterns of feather and scallop prints, and the children’s dresses, pressed flat like paper dresses, hung and swung from the shop fronts.”

To the plants and flowers:

“Soon the bauhinia trees would bud along the road, their flowers white and curved like shells. Now the fields were dry, but each side of the road was water left from the flood that covered the plain in the rains; it showed under the floating patches of water-hyacinth and kingfishers, with a flash of brilliant blue, whirred up and settled on the telegraph wires, showing their russet breasts.”

As a twenty-first century reader, I’m reading at a very different time to when The River was written, and I do approach Godden’s novels set in India with some trepidation. We know that imperialism and colonialism underpin this fictional family’s way of life. While Godden was definitely a product of this herself, I found the descriptions in this novella evocative rather than exoticising. I didn’t get a sense of othering in The River but maybe a more astute reader would. Harriet views India as home although she is aware she doesn’t wholly fit in.

The natural environment and Harriet’s developing identity come together when she has an almost mystical experience by the cork tree in the garden:

“She put her hand on the tree and she thought she was drawn up into its height as if she were soaring out of the earth. Her ears seemed to sing. She had the feeling of soaring, then she came back to stand at the foot of the tree, her hand on the bark, and she began to write a new poem in her head.”

Although Harriet is infatuated with Captain John – a man injured both physically and psychologically by the war – it is her love affair with words that comes through so strongly. It’s a profound portrait of a child who will grow into a writer and how deeply the vocation is felt within her.

I think even if I hadn’t read the preface, the sense of how Godden came to write this is so clear. It is someone trying to evoke a place and life close to their hearts, with an awareness it has gone forever. The River is a quick read, not plot heavy, but a distinctive and memorable portrait of the gains, pains, lessons and losses of growing up.

Jean Renoir adapted The River in 1951 but the trailer seemed to me to be taking a very different tone to the book. I don’t know if this is reflective of the film itself, but it means it’s back to 80s pop videos! Regular readers of my witterings will not be at all surprised at the song choice to finish this post: