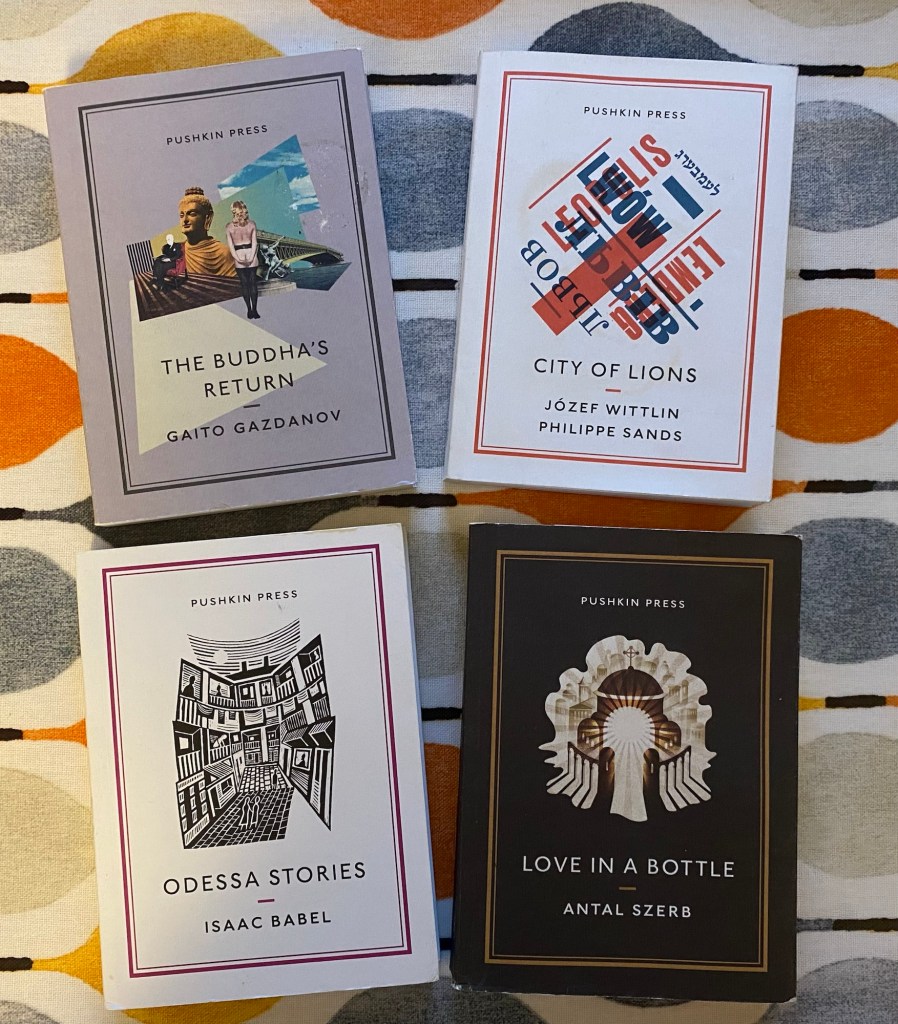

This week I thought I’d use Kaggsy and Lizzy’s #ReadIndies event to focus on one indie publisher, and finally get to four books that have long been languishing in the TBR. Pushkin Press “publish some of the twentieth century’s most widely acclaimed and brilliant authors” and they are one of my favourite indies, ever-reliable. Which hasn’t stopped four from their Collection series remaining unread by me for far too long!

Today I’m starting with The Buddha’s Return by Gaito Gazdanov (1949-50, transl. Bryan Karetnyk 2014). Gazdanov was a Russian writer exiled in France and this short novel, described by the publishers as “part detective novel, part philosophical thriller, and part love story” is set in Paris, as much as it is set anywhere – reality is not a consistent concept in this story at all.

The narrator is a student who is experiencing prolonged periods of hallucinations. He tells us from the start that he is an unreliable storyteller:

“Nowhere was there any logical pattern in this, and the shifting chaos clearly failed to present even a remote semblance of any harmonious order. And so, accordingly, at that point in my life, which was marked by the constant attendance of chaos, my inner existence acquired an equally false unwavering character.”

We slide back and forth between a recognisable reality of his poverty-stricken life in Paris and his disturbing, disorienting visions, without always knowing which is which. Early on in the novel he falls to his death from a sheer mountainside, later he is arrested and interrogated by the Central State. The government’s accusations of treason are entirely surreal and illogical, yet this is also what makes them horribly believable.

There is political commentary running through the novel, but the kaleidoscopic nature of the narrative means it is not a sustained satire on any particular country, ruler or party, but rather a wider condemnation:

“The ignorant, villainous tyrants who so often ruled the world, and the inevitable and loathsome apocalyptic devastation apparently inherent in every era of human history.”

Around halfway through, more of a plot emerges as Pavel Alexandrovich, an older man whom the student befriended, is murdered and his golden statuette of Buddha stolen. As the last person to see Alexandrovich alive, the student falls under suspicion. The real-life interrogation by the investigators has shades of the surreal fantasy interrogation by the Central State:

“If we can find the statuette, you’ll be free to return home and continue your research on the Thirty Years War, the notes on which we found in your room. I must say, however, that I completely disagree with your conclusions, and in particular your appraisal of Richelieu.”

As that quote shows, there is humour in The Buddha’s Return and this lightens a tale which has a lot of dark elements: visceral war scenes, squalor, and of course murder.

Apparently, The Buddha’s Return was originally published in instalments and I can see it would work well in this format. I enjoyed it but for me the more plot-driven second half arrived at just the right time, when I’d started to feel it was losing momentum. As it was I enjoyed this consistently surprising tale which still had enough recognisable humanity in it to be involving, and I’d be keen to read more by Gazdanov.

“I have a suspicion that you just dreamt the whole thing up. It’s because you read too much, eat too little and spare hardly any thought for the most important thing at your age: love.”