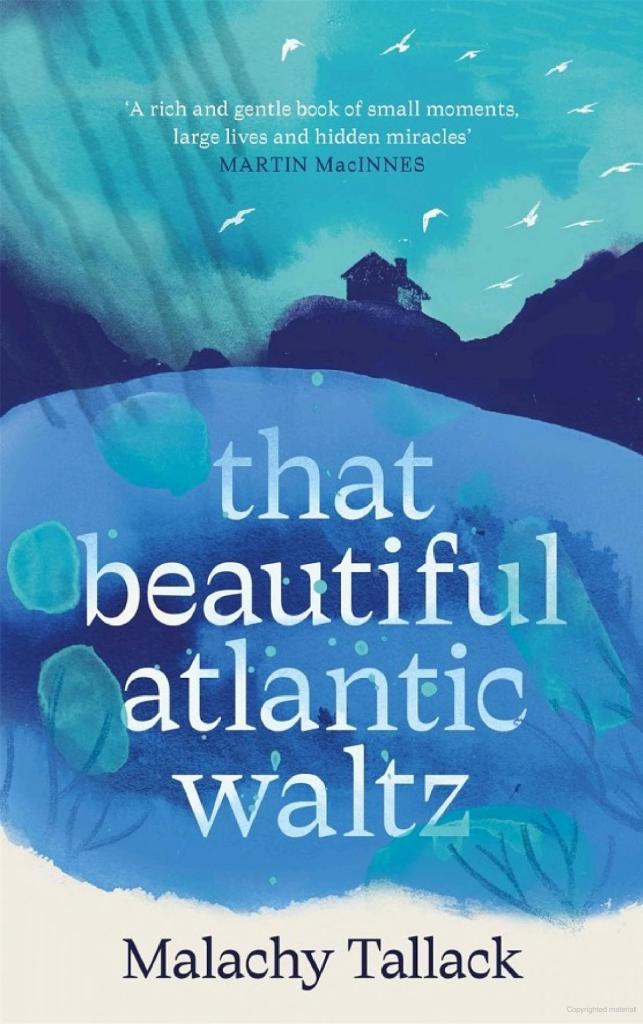

I wanted to read That Beautiful Atlantic Waltz by Malachy Tallack (2024) ever since I heard about it on Susan’s blog where it also made her Books of the Year. Everything about it appealed: the Shetland setting, the portrait of a life quietly lived, the theme of friendship and the concise but descriptive style. My hopes were ridiculously high; they were also fully met.

There are two timelines, one which begins in the late 1950s with Sonny on a whaling ship, following his marriage to Kathleen and family life with their son Jack and her uncle Tom, ending in the 1970s. The other follows solitary Jack in late middle-age, in the present day.

Apart from a brief few weeks in Glasgow, Jack has always lived in the same house on the croft in Shetland:

“He had so many memories of this room that it seemed not separate from him at all but a part of who he was and who he had always been. He had done so much of his living in this room.”

He is for the most part content with his life: taking walks, keeping his part time job ticking over, listening to his beloved country music and writing songs no-one will hear.

Tallack is a musician and he writes beautifully about music and all it can mean to people; how listening to it can be transcendental and how writing it can be a solitary act which simultaneously opens you up to the world. Jack’s handwritten songs punctuate the story and expand his portrayal beyond his immediate situation.

“To love was an act of imagination. It was to create possible futures, to build new and better selves. When love ended, those futures and those selves were what was lost. Jack knew something of loving from writing love songs. And he knew something of heartbreak, too.”

Jack is not especially damaged or traumatised, but he is a man whose solitary nature has found a space where it is never needed to be otherwise. He grew up in a house where feelings, worries and hopes were not discussed. His father Sonny is a man quick to anger who finds:

“So often feelings came to him like that: in a knot he was ill equipped to undo.”

While his more gregarious mother Kathleen doesn’t know how to broach her son’s silence:

“She listened, feeling the tears creep down her cheeks, not thinking of anything in particular, just hearing that cumbersome music, with a closed door between herself and her son.”

Life changes for Jack when someone leaves a kitten on his doorstep. He doesn’t want the cat but sometimes we share our lives with those we could never imagine choosing, and so Jack finds himself no longer living alone but with energetic, cheeky Loretta (named after Lynn). And his life begins to expand in ways he could not foresee.

In That Beautiful Atlantic Waltz, Tallack has crafted a story of such humane understanding and kindness. It isn’t remotely sentimental in its portrayal of the capacity of human beings to reach one another and to change.

An absolute gem.

To end, the author performing his titular song: