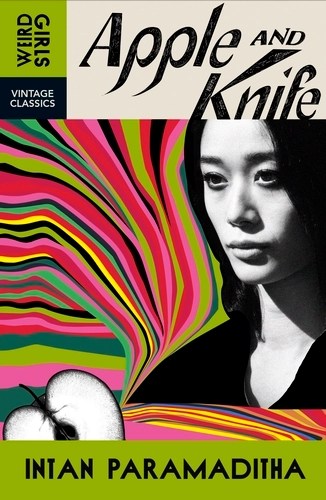

I’m determined to finish my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge this year, and yes, I did say that last year too 😀 It has got more challenging as time has gone on because I’m dependent on what has been translated, so I was delighted to find Indonesian writer Intan Paramaditha included in the Vintage Classics Weird Girls series (even if I do bristle a bit at the condescending title).

Apple and Knife (2018, transl. Stephen J Epstein 2018) is a collection of short stories, mostly set in the modern day but quickly destabilised into gothic, fairytale (in the Grimm sense) realities. They are united by a visceral, forthright sensibility.

“I want drops of blood to be ink on my book, encrusted in the lines of destiny that twist and spin history on my palm. I want to make sacrifices like blood does, play with puddles, ooze sores, flare in anger.”

The collection opens with The Blind Woman Without a Toe, a reworking of the Cinderella story, told from the point of view of one of her step-sisters. This put me in mind of fellow Weird Girls author Angela Carter, particularly The Bloody Chamber. However, Paramaditha’s voice is resolutely her own, and part of the impact of the horror occurs because a recognisable reality grows uncontrollably into something dark and unmanageable.

I’m always interested in portrayals of witches, those women who live on the fringes and often offered women healthcare. In Scream in a Bottle, Gita is a researcher who travels to Cadas Pangeran in search of a witch named Sumarni.

“It’s as if time is gnawed away by termites here. The hours melt into the night, and the tick of the clock no longer matters.”

It soon emerges that Sumarni’s main work is ending unwanted pregnancies.

“She seems almost a smile, but no smile is reflected in her grey eyes. Gita watches as those eyes become the sky. Clouds gather within; they let loose rain, but no thunder.”

As this story develops across a few pages, Sumarni explains an element of her work that is otherworldly, both menacing and protective, a commentary on the silencing of female voices and experience. It is deeply unnerving.

One of the most disturbing tales for me was Beauty and the Seventh Dwarf, which features violent (consensual) sex and self-mutilation. But I never had the sense that Paramaditha was being gratuitously shocking. She uses the bloody and the violent to explore the insidious control of women’s bodies in the modern world; the fabulist framing highlighting recognisable horrors rather than obscuring them.

“Bathed in the blue glow, her mangled features made me feel as though I was looking at a mermaid who had been dashed against the rocks by the waves. Yet I was shipwrecked, and she was not rescuing me.”

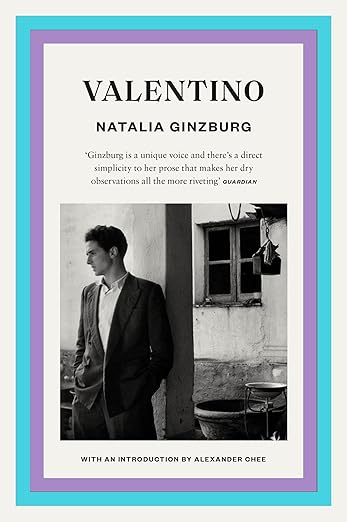

I’ve only scratched the surface here of the settings and themes in the collection, but hopefully I’ve given a flavour of what to expect. Not a comfort read but an interesting one! I’d like to read longer fiction by this author now, to see what she does with more space to explore. Luckily her first novel has also been translated: