I really want to increase my blogging in 2023 – as I’m an incredibly strong-willed person who always achieves any goal they set, I have absolutely no doubt I will achieve this aim 😀

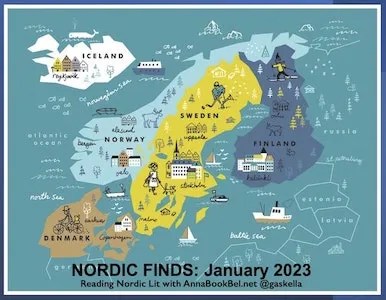

Anyway, the wonderful reading events that take place are always an incentive to help me on my way, and in January Annabel runs her enticing Nordic FINDS month.

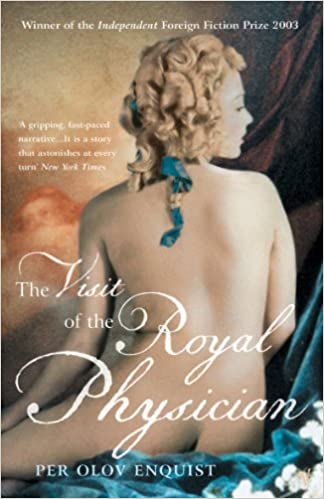

This meant that I have finally pulled a book from the TBR that has been languishing there for years: The Visit of the Royal Physician by Swedish author Per Olov Enquist (1999 trans. Tiina Nunnally 2001). A historical novel set in the 18th-century Danish courts, it tells the story of King Christian VII’s mental ill health, his marriage to Caroline Mathilde (sister to George III) and her affair with the titular German doctor, Johann Friedrich Struensee.

TVOTRP is hugely lauded, winning the August prize and the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. This meant I went in with unfairly high expectations and at first I wasn’t sure this novel was for me. I suppose TVOTRP would be classed as a documentary novel, and initially I found this style distancing. However, by the end I was very much involved in this sad tale of people sacrificed to political power struggles where there is no room for humanity.

Even if the historical events are unfamiliar, the reader knows it will end with the execution of Struensee, as this is where the novel begins. We’re then taken back to his arrival at court, a man of the Enlightenment, viewed with some degree of suspicion by those resistant to change.

King Frederik V dies in his forties, and there is a vivid scene of him on his deathbed with his son, being abusive until the end. Christian is sixteen when he becomes King Christian VII and he is already struggling to comprehend reality.

“Christian explained, in a stubborn attempt to make sense of things, that he understood the court to be a theatre, that he had to learn his lines, and that he would be punished if he didn’t know them by heart.”

But was he one person or two?”

Enquist demonstrates so clearly that it would be some sort miracle if Christian managed to stay well in the environment of the court. He is not only abused by his family but by the courtiers; he is physically and mentally tortured.

Caroline Mathilde is 15 when they marry.

“Afterwards everyone agreed that it was unfortunate that she did indeed have talents. If the proper assessment had been made from the outset, namely that she possessed some talents, then the entire catastrophe might have been averted.

But no one could have predicted this.”

These teenagers are not expected to rule Denmark. They are expected to be figureheads and provide heirs, and not get in the way of the power-hungry politicians that surround them. When Struensee arrives in court, he poses a huge threat despite not appearing to want power at all. Firstly, he genuinely cares about Christian:

“It was understood that something had happened. The German doctor with the blonde hair, the quick but wary smile and the kindly eyes, had become somebody. Since he had no title and could not be placed within a precise hierarchy, this caused uneasiness.

Attempts were made to decipher him. He was not easy to decipher. He was friendly, discreet, and refused to make use of his power, or at least what was considered to be power.

People didn’t understand him.”

Secondly, he is a man of the Enlightenment, deeply threatening to Puritan courtiers like the advisor Guldberg, who is slowly growing his influence. Thirdly, he sleeps with the Queen:

“Christian, Caroline Mathilde, Struensee. Those three.

They seem to be observing each other with curiosity and suspicion. The court observed them too. As they observed the court. Everyone seemed to be waiting.”

The tension builds as the reader knows this situation will absolutely not be tolerated. And it seems such a travesty. The King is happy and cared for; the Queen is happy and fulfilled; the person taking decisions on behalf of the ruler is progressive, liberal, and trying to improve the situation of the masses. Why not let it continue?

Struensee is not naïve and he is filled with a sense of foreboding. Meanwhile, Caroline Mathilde seems to believe they can outwit the malevolent forces that are closing in…

“Her analysis surprised him.

He thought that her extremely lucid, extremely brutal view of the mechanisms of power had been born at the English court. No, she told him, I lived in a cloister. Then where had she learned all this? She was not one of those that Brandt, with some scorn, used to call ‘the female schemers’.

Struensee understood that she saw a different kind of pattern to his.”

The style of TVOTRP is really interesting. As I mentioned earlier, it’s a documentary style, but with an omniscient narrator so there is space given to the feelings and motivations of all the characters. The sentences are generally choppy, but often also poetic. Enquist balances these opposing approaches expertly. I never quite got past that initial distance I felt and so this stopped me absolutely loving the novel, but I did think it was an excellent and compassionate exploration of the pressures of public life and the dangers for those trying to change entrenched power structures.

Although not a depressing novel, it did seem desperately sad, for all concerned.

“The revolution that Struensee initiated was quickly stopped. It took only a few weeks for everything to revert to the way it was before, or to even earlier times. It was as if his 632 decrees, issued during the two years known as the ‘Struensee era’ were paper swallows, some which landed, while others were still hovering low over the surface of the field and hadn’t yet managed to alight on the Danish landscape.”

To end, I saw A Royal Affair (which tells the same story but isn’t an adaptation of this novel) when it came out in 2012. I don’t remember much of it now but I do remember enjoying it and thinking all three leads were excellent. From this trailer I would say Christian is portrayed less sympathetically than Enquist saw him, but it definitely looks worth a re-watch: