Well, as I predicted a significant part of my May was grim, but at least it was short-lived. So while I couldn’t commit to my novella a day in May project this year, I have managed to read a few novellas which I’m hoping to blog on before the end of the month. Here’s hoping June is a massive improvement!

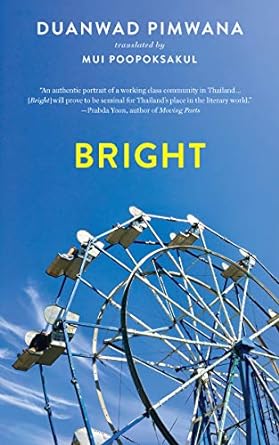

When I undertook the Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge, I wanted each book to be by an author from that country, not only set there. So the challenge has slowed as I try and locate appropriate translated fiction. Bright by Duanwad Pimwana (2002 transl. Mui Poopoksakul 2019) was apparently the first novel by a Thai woman to be translated into English. A volume of her short stories has also been translated, under the title Arid Dreams.

Bright almost reads like a series of short stories, except that the characters and setting are carried across the vignettes. It begins with a five-year-old boy, Kampol, being abandoned by his father who is taking his little brother Jon to live with his grandmother after their mother has left. But Bright isn’t unremittingly grim or a trip into poverty porn. The community of Mrs Tongan’s tenements rally round Kampol with varying degrees of willingness to ensure the boy is cared for.

“Kampol watched his father walk off until he disappeared. The flavour of the palo stew had grown distant, and the scent of detergent faint. He opened his hand: the blue action figure glinted in the dim light.”

We meet the various residents through Kampol’s eyes and we follow the events of the community alongside him. He plays with his best friend Oan, and is often cared for often by Oan’s hardworking mother Mon. But Pimwana never lets us forget that Kampol is carrying a lot of pain, just below the surface.

“He had found the best hiding place: you’d have to travel back in time to discover it. He skipped away joyfully. But then his melancholy caught up to him and his steps grew slow and measured – he didn’t know where to go.”

My heart sank when mobile caterer Dang offers Kampol a way to earn money if he keeps it quiet – but Dang only wants Kampol to walk on his back to relieve his aching muscles. Kampol also earns money running errands for soft-hearted Chong, the shopkeeper who finds it hard to refuse people credit. Bookish Chong was my favourite character, a man trying to convince the local kids of the joy of the printed word, without much success apart from Kampol.

“Chong was mournful as he watched the tree-cutting operation. The workers sawed off one section at a time, starting from the crown and working their way down. The pines disappeared, one top at a time, one tree at a time. Kampol stood next to Chong staring upward until the sky was empty. The notion of his mother, too, grew empty in his mind.”

The simple writing style worked really well in keeping the reader alongside Kampol while not claiming to be completely a child’s point of view. I found it direct and compelling in portraying a life with both hardships and joys in it.

Pimwana portrays a Thailand away from the tourist hotspots or glamourous settings. In doing so, she never patronises her characters or preaches of a life of either degrading poverty or sentimental saintly striving. The personalities in her pages are entirely believable, human and humane. It’s a fine balance that she achieves with the lightest touch. A hugely impressive and highly readable novella.

“He had felt lonesome before, many times in fact. But in those moments, even if he didn’t have anyone in the world, he had his familiar neighbourhood, with its familiar crevices and corners that he knew so well, which provided comfort. There was the wall outside Chong’s shop, where the jasmine bush stood, marked with dirt from where he leaned against it when he visited. Or there was the wedged fork of the poinciana. Or behind Mrs Tongjan’s house, his hideout beneath the shrub whose leafy branches bowed down and kissed the ground. When desolation struck, Kampol had these familiar nooks to embrace him.”