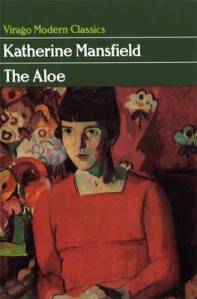

The Aloe – Katherine Mansfield (1916, this edition 1983) 79 pages

The Aloe was Katharine Mansfield’s first punt at writing her short story Prelude, and so while it’s not entirely satisfactory as a fully realised story in its own right, there’s still a lot to enjoy here. It also forms another stop on my Around the World in 80 Days Reading Challenge.

It begins with the Burnell family moving to a new home further out in the New Zealand countryside. The opening is told from the children’s point of view as the three of them are old enough to realise what is happening but too young to take an active part. I thought Mansfield captured the detailed minutiae of children’s lives so well:

“Kezia liked to stand so before the window. She liked the feeling of the cold shining glass against her hot little palms and she liked to watch the funny white tops that came on her fingers when she pressed them hard against the pane”

Once they arrive at the larger, more remote house, the attention shifts to the adults. Mansfield is incredibly subtle in her characterisation, drawing psychologically astute portraits but leaving the reader to work out what it means for this group of people to be living together.

Stanley Burnell is optimistic and eager about the move, little realising the various pressures it places on the women of the household, mainly because he is out in town all day:

“He was enormously pleased – weather like this set a final seal upon his bargain – he felt somehow – that he had bought the sun too and got it chucked in dirt cheap.”

His wife Linda is neither entirely happy nor completely unhappy, but certainly she is part of a generation of women given to mysterious ailments like headaches which enable her to spend a day in a room closed off from the rest of the household. She able to do so because her mother Mrs Fairchild is so capable and domesticated:

“There was a charm and grace in all her movements. It was not that she merely ‘set in order’; there seemed to be an almost positive quality in the obedience of things in her fine old hands.”

One piece of characterisation I really liked was Beryl, Linda’s sister. There is a hint that she may be trying to seduce her brother-in-law, mainly through boredom and a need to feel loved. As she writes a letter to her friend full of news that she knows is insincere, superficial prattle, she has this insight:

“Perhaps it was because she was not leading the life that she wanted to – she had not a chance to really express herself – she was always living below her power – and therefore she had no need of her real self – her real self only made her wretched.”

In lesser hands Beryl would just be a flighty, flirty, dreamer with the potential for real destruction, but Mansfield shows how all the women are forced into certain roles because society doesn’t give them the choices it affords to men. This is never didactic though; the reader is left to draw their own conclusions.

The Aloe only covers two days in this family’s life (though Mansfield ultimately wrote three short stories about the Burnells) but so much is explored, reading it is still a rich experience. My only reservation is that my delicate sensibilities could have done without the duck-killing scene (which I skimmed.) The novella does end rather abruptly but then it was never quite intended to be read as it is now.