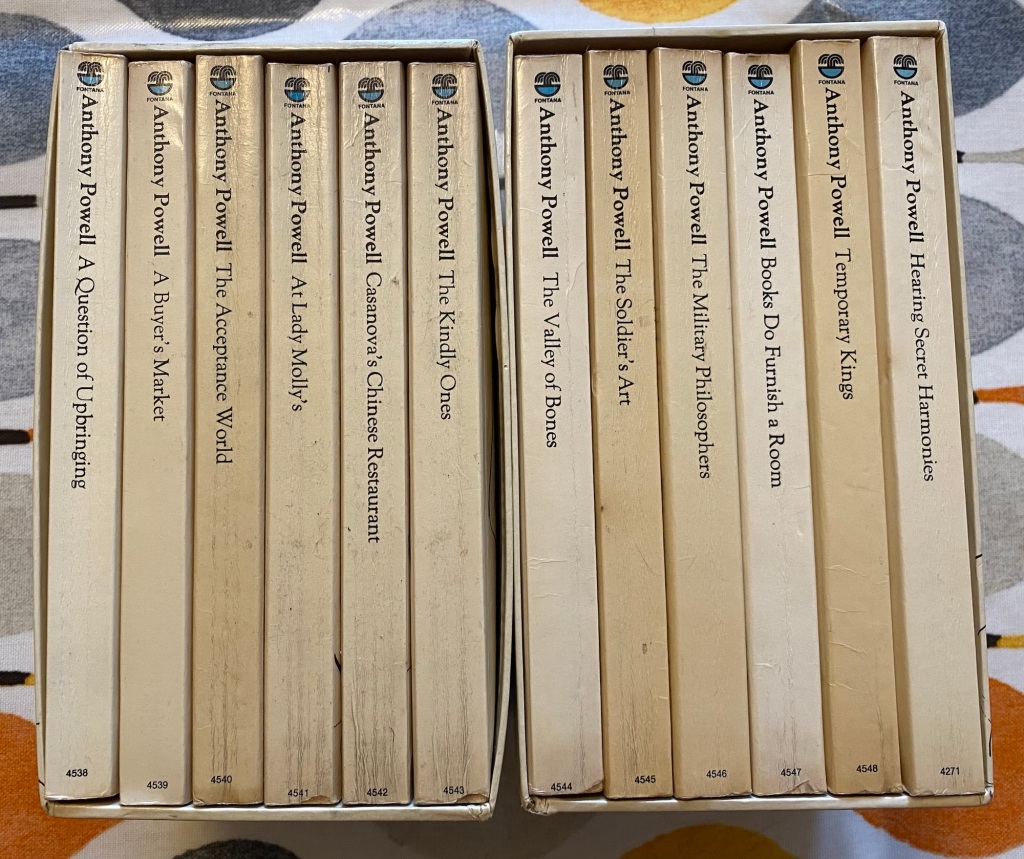

This is the seventh instalment in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

The seventh volume, The Valley of Bones, was published in 1964 and is set at the start of World War Two, when Nick has joined the army as an officer.

I’ve said when reading previous novels in the sequence that I’m intrigued by Nick’s outsider’s view, as it’s not clear where it comes from since he seems so much a part of the society he portrays. In the army, the distinction is clearer. Nick finds himself billeted to South Wales within a company made up mostly of bankers, very different to his bohemian artsy London life.

“I indicated that I wrote for the papers, not mentioning books because, if not specifically in your line, authorship is an embarrassing subject for all concerned.”

Nick casts his sharp eye over these new associates in the same way he has for his friends, family and acquaintances up to this point. A central character is Captain Rowland Gwatkin, a man who seems simultaneously devoted to the army and entirely bewildered by it too:

“Gwatkin lacked in his own nature that grasp of ‘system’ for which he possessed such admiration. This deficiency was perhaps connected in some way with a kind of poetry within him…Romantic ideas about the way life is lived are often to be found in persons themselves fairly coarse- grained.”

Gwatkin is really tightly wound, and there is a sense of impending doom at best, destruction at worst with him.

Nick is an indifferent soldier, neither very good nor absolutely awful. There is some consideration of philosophical theories of war, but primarily Nick is interested in those who surround him:

“It is a misapprehension to suppose, as most people do, that the army is inherently different from all other communities. The hierarchy and discipline give an outward illusion of difference, but there are personalities of every sort in the army, as much as out of it.”

Powell brilliant portrays the simmering tensions in the company, both from the mix of personalities attempting to work together within and the increasing threat from Hitler without. There are those with alcohol problems, death by suicide, and broken hearts, yet the days mostly pass in utter tedium. Nothing changes even after the company is uprooted to a posting to Northern Ireland:

“At Castlemallock I knew despair. The proliferating responsibilities of an infantry officer, simple in themselves, yet, if properly carried out, formidable in their minutiae, impose a strain in wartime even on those to whom they are a lifelong professional habit; the excruciating boredom of exclusively male society is particularly irksome in areas at once remote from war, yet oppressed by war conditions.”

As Adjutant Maelgwyn-Jones observes: “That day will pass, as other days in the army pass.”

Yet there is some light relief too, such as an inspection from a visiting General, seemingly obsessed with breakfast foodstuffs:

“The General stood in silence, as if in great distress of mind, holding his long staff at arm’s length from him, while he ground it deep into the earth the surface of the barnhouse floor. He appeared to be trying to contemplate as objectively as possible the concept of being so totally excluded from the human family as to dislike porridge.”

And Nick does get some weekend leave in order to catch up with his family. There he finds people thrown together, behaving oddly and under strain. In other words, not so very different from his army posting. As his pregnant wife Isobel observes: “the war seems to have altered some people out of recognition and made others more than ever like themselves.”

In The Valley of Bones Anthony Powell shows himself uninterested in the glorification of war or in any sort of jingoism. He also doesn’t fall into the trap of a wholly satirical, detached point of view either. He manages a delicate balance between conveying the seriousness of war alongside the human inadequacies and frailties of those expected to enact it.

He also pulls an absolute masterstroke at the finish. The boredom, the admin, the essentially unthreatening – if somewhat self-destructive – colleagues are turned upside down in an instant, and Nick finds himself carried forward, powerless in a situation about which he has a deep sense of foreboding. It’s a chilling ending and I’m anxious to see how it plays out in the next volume, The Soldier’s Art.

“In the army – as in love – anxiety is an ever present factor where change is concerned.”

To end, a song absolutely synonymous with wartime Britain for many, which seems particularly apt for Nick as he’s always running into people he met previously: