Happy Colette’s birthday! I love her writing, and so I somewhat erratically try and post on her birthday. This year I decided it was a perfect impetus to finally get to her memoir The Evening Star (1946 transl. Peter Owen 1973) which has been languishing in the TBR for too long…

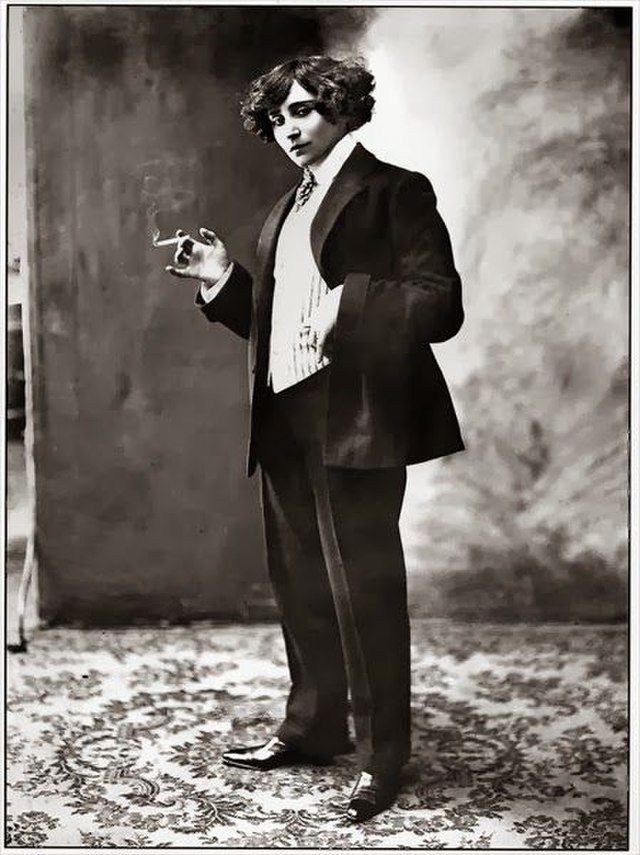

Image from here

This memoir was written when Colette was in her seventies and experiencing significantly reduced mobility, due to arthritis. She remains sanguine:

“If we are to be shaped by misfortune, it’s as well to accept it. We do well to adapt misfortune to our requirements and even to our convenience. This is a mode of exploitation to which the young and robust are ill-suited, and I can well understand the difficulty of making them appreciate, for instance, that near-immobility is a gift.”

She is at home in the Palais-Royal:

“When I am alone, my apartment relaxes. It stretches itself and cracks its old joints. In fine dry weather it contracts, retracts, becomes immaterial, the daylight shows under all its doors, between its every hinge and joint. It invites the wind from outside and entrusts my papers to it, they go skimming off to the other end of the room. I shan’t unwind my cocoon of bed clothes for their sake. Greedy for air, I am a coward when it comes to cold.”

Her humour remains undimmed, such as after a long, poetic contemplation on pink in nature, she concludes:

“Enough of this blandness. I could enjoy a pickled herring.”

And I also enjoyed this reflection on her process:

“On the strength of those writers who do make notes, I had made notes on a sheet of paper, and lost the paper. So I bought a notebook, American style, and lost the notebook, after which I felt free, forgetful, and willing to answer for my forgetfulness.“

Written in 1946, Colette considers her home and city in the immediate aftermath of Nazi occupation:

“In its urbane, sly, stubborn fashion, the Palais-Royal began its resistance and prepared to sustain it. What resistance, what war can I speak about other than those I have witnessed?”

(Colette’s husband was Jewish and had been taken by the Gestapo, but subsequently released. He remained in a degree of hiding with the help of her Palais-Royal neighbours).

“All that offered itself insidiously, or made use of violence, Paris rejected equally. Let us caress with a happy hand it’s still-open wounds, it’s upset pillars, it subsided pavements: its wounds apart, it emerges from all this intact.”

Memories ebb and flow, and Colette reflects this in her writing. This is not an ordered – either chronologically or thematically – memoir. It is more a series of reflections and reminiscences, the past and present layered upon each other. There were times when I lost the thread of exactly what she was saying but just let her hypnotic prose wash over me. This felt an appropriate way to experience her memories and a clever way for Colette to align the reader with her experience as she reflects and writes from her bed.

I find some of Colette’s views problematic but these passages are short-lived. My favourite part of Colette’s writing is always how she captures her love of nature, and even from within her Parisian apartment she engages with the natural world. (Her husband occasionally intervenes in the narrative and is referred to as “my best friend”):

“My best friend, how can you think that I might have been bored? Why, the sky alone is distraction enough.”

There’s plenty here I haven’t mentioned and Colette’s discussion of friends and colleagues would also be of interest to anyone who enjoys early twentieth century French literature. It’s a short work, just over 140 pages in my edition, but such a joy to spend time with Colette.

I’ll leave you with this short quote, helpful for those of us in the Northern hemisphere currently enduring a January at least 84 days long…

“What should I wait for, if not the spring?”