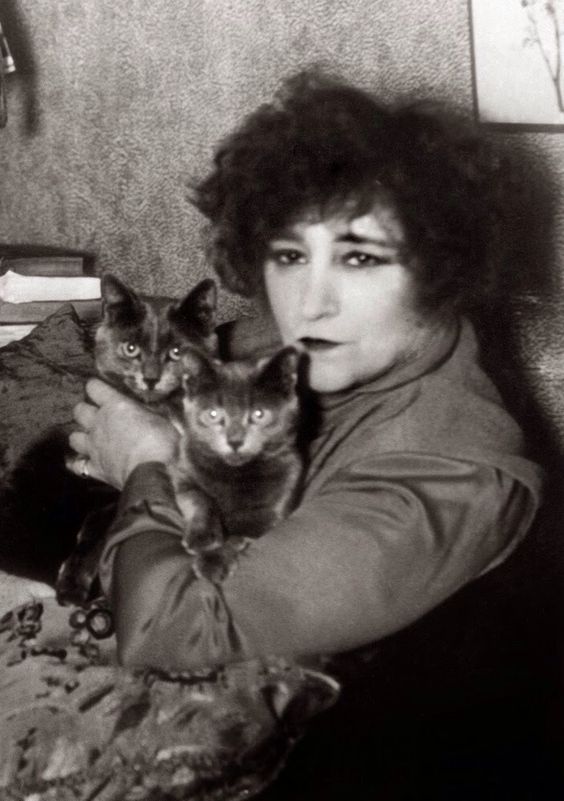

Mallika at Literary Potpourri’s wonderful event Reading the Meow has been running all week, do check out all the great posts prompted by our feline friends! Here is my post just in time…

I’m grateful to Reading the Meow for finally getting me to pick up The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (finished in 1940, published in 1966) which is part of my Le Monde’s 100 Books of the Century Reading Challenge and has been languishing in my TBR for years. Although not ostensibly a book about cats, one does feature prominently as these various edition covers will attest:

The reason it had lain unread for so long was because I’m (aptly) a big scaredy-cat. I was really intimidated by this classic of twentieth-century fiction and I thought it would be far too complex and clever for me to understand. Which as it turned out, was broadly correct. I’m sure I didn’t pick up all the allusions and references, even with the notes in the back of my edition to help me (Alma Classics, trans. Hugh Aplin 2020 – I definitely recommend this edition and translation). However, I still found it very readable and a lot to enjoy, especially regarding Behemoth, the character that meant I was reading it this week particularly.

The Devil arrives in 1930s Moscow as a Professor Woland, along with his entourage: red headed, bizarrely dressed Korovyev; sinister vampiric Azazello; beautiful Hella; and Behemoth, an enormous cat that walks on his hindlegs, talks, drinks vodka and plays chess.

The proceed to wreak havoc for three days in a series of carnivalesque scenes, using the greed and corruption of people against them. It’s absolute chaos and carnage, but brilliantly Bulgakov shows that the devil doesn’t have to push very hard for all this to occur.

At the start of the novel, Woland predicts the shocking and absurd death of Berlioz, head of Massolit, a literary organisation. Once people hear of his death, this description of a barrage of statements in order to get Berlioz’s apartment is a good example of how Bulgakov balances social realism, satire, the comic and the desperate throughout:

“In them were included entreaties, threats, slanders, denunciations, promises to carry out refurbishment at people’s own expense, references to unbearably crowded conditions and the impossibility of living in the same apartment as villains. Among other things, there was a description, stunning in its artistic power, of the theft of some ravioli, which had been stuffed directly into a jacket pocket, in apartment No.31, two vows to commit suicide and one confession to a secret pregnancy.”

Meanwhile, Margarita, beautiful and unhappily married, is distressed because her lover, The Master, has committed himself to an institution and renounced his writing.

This is interspersed with the story of Pontius Pilate and Yeshua (Jesus), with the two stories echoing one another, and it emerges that this was the novel The Master was writing.

It is through the titular characters that Bulgakov prevents his satire becoming too bitter and alienating. Their devotion to each other and Margarita’s belief in The Master’s work is truly touching.

I don’t really want to say too much more as The Master and Margarita is such a complex, riotous piece of work that I think the more I try and pin it down the more I’ll tie myself in knots! It tackles the biggest of big themes; religion, state oppression, the role of art, love, faith, good and evil, how to live… It is a deeply serious work that isn’t afraid to be comical too.

But as this post is prompted by Behemoth, here is my favourite scene with him, getting ready for Satan’s Grand Ball on Good Friday and trying to distract from the fact that he is losing at chess:

“Standing on his hind legs and covered in dust, the cat was meanwhile bowing in greeting before Margarita. Around the cat’s neck there was now a white dress tie, done up in a bow, and on his chest a ladies mother-of-pearl opera glass on a strap. In addition, the cat’s whiskers were gilt.

‘Now what’s all this?’ exclaimed Woland. ‘Why have you gilded your whiskers? And why the devil do you need a tie if you’ve got no trousers on?’

‘A cat isn’t meant to wear trousers, Messire,’ replied the cat with great dignity. ‘Perhaps you’ll require me to don boots as well? Only in fairy tales is there a puss in boots, Messire. But have you ever seen anyone at a ball without a tie? I don’t intend to find myself in a comical situation and risk being thrown out on my ear! Everyone adorns himself in whatever way he can. Consider what has been said to apply to the opera glasses too, Messire!’

‘But the whiskers?’

‘I don’t understand why,’ retorted the cat drily, ‘When shaving today Azazello and Korovyev could sprinkle themselves with white powder – and in what way it’s better than the gold? I’ve powdered my whiskers, that’s all!’

[…]

‘Oh, the rogue, the rogue,’ said Woland shaking his head, ‘every time he’s in a hopeless position in the game he starts talking to distract you, like the very worst charlatan on the bridge. Sit down immediately and stop this verbal diarrhoea.’

‘I will sit down,’ replied the cat sitting down, ‘but I must object with regards your final point. My speeches are by no means diarrhoea, and you’re so good as to express yourself in the presence of a lady, but a series of soundly packaged syllogisms which would be appreciated on their merits by such connoisseurs as Sextus Empiricus, Martianus Capella even, who knows, Aristotle himself.’

‘The kings in check,’ said Woland.

‘As you will, as you will,’ responded the cat, and began looking at the board through the opera glass.”

I think overall I probably admire The Master and Margarita more than love it, and I enjoyed Bulgakov’s A Country Doctor’s Notebook more. But there is so much in this extraordinary, unique novel that will stay with me, and I’m sure it will reward repeat readings too.

To end, I tried to get my two moggies to pose with the book. With typical cattitude, they flatly refused 😀 So it’s back to 80s pop videos: