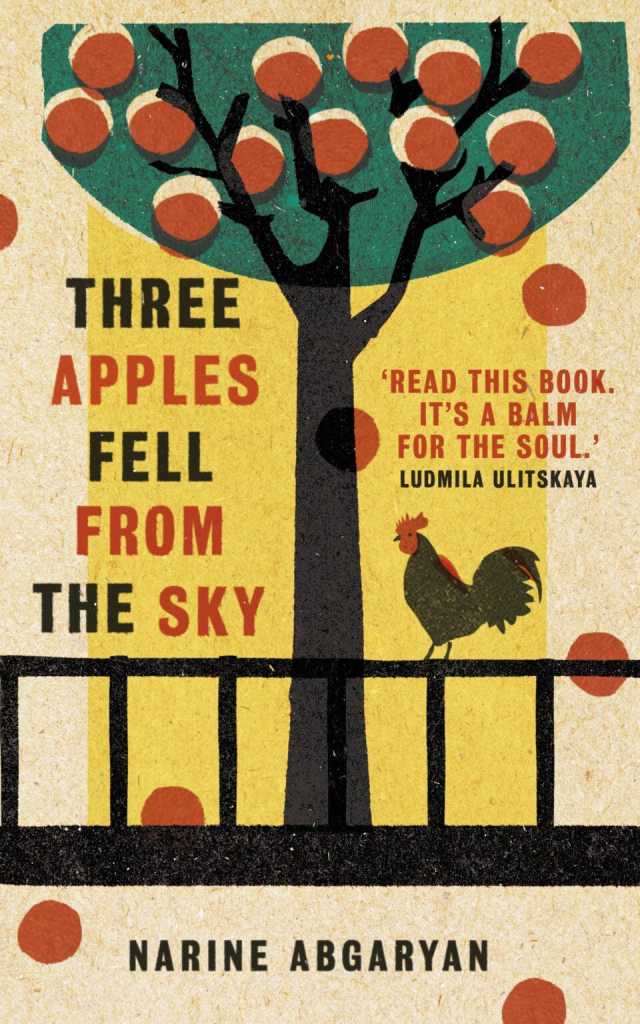

After The Glass Pearls I needed a comfort read, and so I turned to Three Apples Fell From the Sky by Narine Abgaryan (2014, transl. Lisa C Hayden 2020). I had originally picked it up for my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge as it is by an Armenian author and set in a small village in that country, but happily it also works for #ReadIndies hosted by Kaggsy all this month, as it is published by Oneworld.

The story opens with Anatolia Sevoyants, a lifelong resident of the remote clifftop village of Maran, experiencing significant post-menopausal bleeding and deciding her time is up.

“She had decided to die with her dignity and tranquillity intact, in peace and quiet, within the walls of the home where she’d lived her difficult, futile life.”

So rather than see her neighbour and friend Yasaman who is something of a naturopath and healer, Anatolia takes to her bed.

We are alongside as she lays reminiscing about her life. My favourite of these (unsurprisingly) is how Anatolia beautified the library, caring for books, plants, birds and the building in her own unique way:

“After assessing the intolerable heartlessness and arrogance in his treatment of his heroines, she classified Count Tolstoy with other petty tyrants and despots, and stored his fat tomes out of sight to make herself feel better.”

Although Three Apples… is a gentle tale, it is not without violence. Anatolia had an extremely violent and abusive husband, and some animals are treated badly at times, which I skipped.

But this all occurs towards the first third of the book, and soon it settles into its tale of Anatolia’s unexpected recovery and even more unexpected life events, amongst the fellow older inhabitants of the village and the drama and domesticity of their lives.

“The village was meekly living out its last years as if condemned, Anatolia along with it.”

There is a fairytale quality to the story as the village is entirely cutoff, the residents grow older with no new generation, white peacocks make an appearance, and this pastoral world is touched at moments by magical realism.

But any magical occurrences or whimsy is tempered by what the villagers have to face; mudslides, war and famine. These are evocatively described and devastating. The stoicism of the villagers is never undermined by a sense that these events are not very real in their destruction.

“And that was how she aged, slowly and steadily, alone but contented, surrounded by ghosts dear to her heart.”

Three Apples… expertly balances fabulism with a grounded reality. Lives are tough, but also filled with love and friendship. Among despair is the surprise of new hope.

It’s also worth mentioning that part of the resilience is food, prepared with love for friends, family and neighbours. There were so many delicious dishes described in this novel! It’s definitely not one to read when you’re hungry – it had me googling ‘local Armenian restaurants’ 😀

“That’s probably how things are supposed to be because that’s just the way it is.”