The 2016 Olympics have come to an end (boo!) but we still have the Paralympics to come (hooray!) There have been astonishing achievements by those who seem to have been made from very different stuff to us mere mortals. When they seem doused in more than their fair share of charisma as well, you can’t even make yourself feel better by thinking that they’re probably horrible people, because they’re just so funny and charming about it all. Who could I be thinking of….?

Human being 2.0

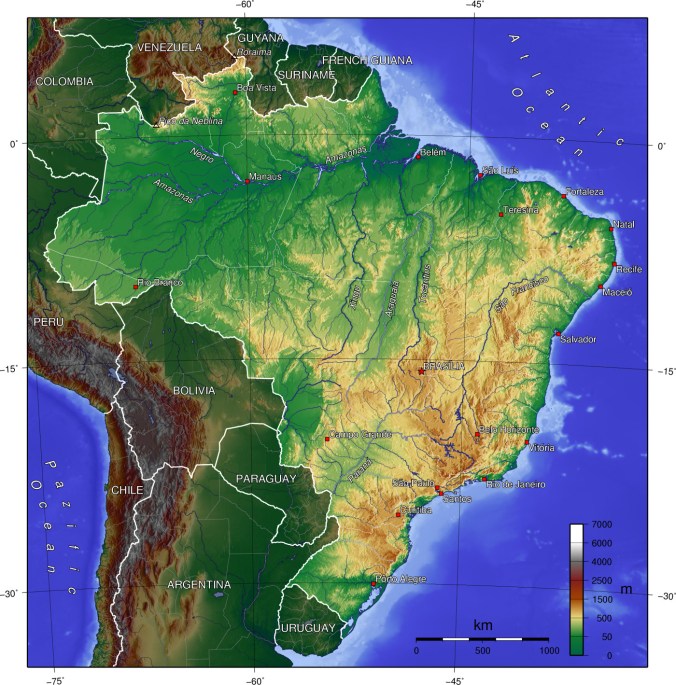

To celebrate the Olympics, I thought I’d take up triathlon sit on my backside reading, of course. It’s Women In Translation Month (head over to Meytal’s blog to read all about WITmonth) so I’m looking at two novellas by Brazilian women writers. This will also be one more stop on my Around the World in 80 Books Reading Challenge, hosted by Hard Book Habit.

Firstly, Agua Viva by Clarice Lispector (1973, tr. Stefan Tobler 2012). Although I’ve called this a novella, I’m not sure that’s really what it is. It’s a series of impressions and observations, plotless but definitely not artless.

“This is life seen by life. I may not have meaning but it is the same lack of meaning that the pulsing vein has.”

I say it’s not artless, because although Agua Viva can give the impression of randomness, it’s carefully constructed to carry you through, the different passages building on and echoing one another.

“So writing is the method of using the word as bait: the word fishing for whatever is not word. When this non-word – between the lines – takes the bait, something has been written…so what saves you is writing absentmindedly.

I don’t want to have the terrible limitation of those who live merely from what can make sense. Not I: I want an invented truth.”

“I notice that I’m writing as if I were between sleep and wakefulness.”

Agua Viva quite a difficult work to talk about, because it resists being pinned down. I could attach various labels to it: impressionistic, modernist, stream-of-consciousness, but none of these are quite right. On this reading – for I suspect it changes every time you read it – I felt it was about trying to capture the immediate present, to pin down moments knowing that they are gone forever just as you recognise them. The style lends itself to this theme, as it jumps and disorientates, on occasions tipping over into surrealism:

“I am feeling the martyrdom of an untimely sensuality. In the early hours I awake full of fruit. Who will come to gather the fruit of my life? If not you and I myself? Why is it that things an instant before they happen already seem to have happened? It’s because of the simultaneity of time. And so I ask you questions and these will be many. Because I am a question.”

I read Agua Viva cover to cover, and I do wonder if this was the wrong approach. While the kaleidoscopic style and images build towards an overall impression, Agua Viva would equally lend itself to being dipped into, reading a single passage and ruminating on it. Apparently the Brazilian singer Cazuza read Agua Viva 111 times. I suspect it’s that sort of book: either you hurl it against the wall within minutes of opening it, or it becomes a mercurial companion for life.

I can’t sum myself up because you can’t add a chair and two apples. I am a chair and two apples. And I cannot be added up.”

Secondly, With My Dog-Eyes by Hilda Hilst (1986 tr. Adam Morris 2014). This is also a disorienting , unsettling work, non-linear and impressionistic. Hilst uses this style to create a highly effective portrait of Professor Amos Keres, who is having some sort of breakdown or psychotic episode. The fractured story-telling serves to take the reader inside the mind of someone who is extremely unwell.

“Poetry and mathematics. The black stone structure breaks and you see yourself in a saturation of lights, a clear-cut unhoped-for. A clear-cut unhoped-for was what he felt and understood at the top of that small hill. But he didn’t see shapes or lines, didn’t see contours or lights, he was invaded by colours, life, flashless, dazzling, dense, comely, a sunburst that was not fire. He was invaded by incommensurable meaning. He could only say that. Invaded by incommensurable meaning.”

The narrative shifts from third to first person as Keres copes with his boss suggesting he take a break, and then spends the day thinking over his life since boyhood, his career and his marriage. This makes it sound more linear and contained than it is, and does With My Dog-Eyes a great disservice. Its power comes from its layering of ideas and images with such rapidity as to almost assault the reader – never incoherent but an effective immersion in an unravelling mind.

“And everything begins anew, the patience of these animals infinitely digging a hole, until one day (I hoped, why not?) transparence inundates body and heart, body and heart of mine, Amos, animal infinitely digging a hole. In mathematics, the old world of catastrophes and syllables, of imprecision and pain was cracking up. I no longer saw hard faces twisting into questions, in tears so many times, I didn’t see the gaze of the other on mine, what a thing it can be to have eyes on your eyes, eyes on your mouth. Waiting for what kind of word? Such formidable cruelties occurring every day, humans meeting and in the good-mornings and good-afternoons such secrets, such crimes, such chalice of lies…”

It’s a good job this was a novella (59 pages in my edition) as I don’t think I could have taken much more of it (that’s a recommendation, not a criticism). With My Dog-Eyes is a short, sharp, shock: a plunge into madness.

To end, I was very excited that Caetano Veloso was performing at the Olympic opening ceremony, but I don’t think the acoustics did him any favours in capturing his wonderfully sensitive voice. Here he is as part of the Pedro Almodovar film Hable Con Ella (Talk to Her):