A Month in the Country – JL Carr (1980) 85 pages

A Month in the Country is why I read novellas: beautifully written, acutely observed, exploring huge themes in a tightly constructed story that is an absolute gem.

Set just after World War I, shell-shocked soldier Tom Birkin arrives in the Yorkshire town of Oxgodby to uncover a medieval mural in the local church, much to the consternation of Reverend Keach:

“ ‘It wasn’t in the contract,’ he hedged, somehow managing to imply that neither were my stammer and face-twitch.”

[…]

“I looked like an Unsuitable Person likely to indulge in Unnatural Activities who, against his advice, had been unnecessarily hired to uncover a wall-painting he didn’t want to see, and the sooner I got it done and buzzed off to sin-stricken London the better.”

Tom hopes that a quiet summer of regular work, quiet and solitude will help him heal:

“The marvellous thing was coming into this haven of calm water and, for a season, not having to worry my head with anything but uncovering their wall-painting for them. And, afterwards, perhaps I could make a new start, forget what the War and the rows with Vinny had done to me and begin where I’d left off. This is what I need, I thought – a new start and, afterwards, maybe I won’t be a casualty anymore.

Well, we live by hope.”

He is employed due to a legacy, which has also employed another soldier, Moon, to find a grave just outside the church walls. Moon works out pretty quickly where the grave is so spins out his task to enable him to excavate remains he has identified at the site. The two recognise one another as kin due to their war experiences, without discussing what happened to either of them.

“This was a fairly typical beginning to most days – a mug of tea in Moon’s dug-out, usually not saying much, while he had a pipe… he would look speculatively at me. Now who are you? Who have you left behind in the kitchen? What befell you Over There to give you that God-awful twitch? Are you here to try to crawl back into the skin you had before they pushed you through the mincer?”

Carr writes about the technicalities of restoration so cleverly. Details are included to make Birkin’s voice authentic, but without it being overwhelming or seeming clunky. What he also captures is Birkin’s love of his work:

“But for me, the exciting thing was more than this. Here I was, face to face with a nameless painter reaching from the dark to show me what he could do, saying to me as clear as any words ‘If any part of me survives from time’s corruption, let it be this. For this is the sort of man I was.’”

Birkin makes friends with residents in Oxgodby: Mr Ellerbeck the station master, his young daughter Kathy, and Anne Keach, the reverend’s wife, who seems as lost as Tom. Written from the point of view of Birkin looking back, there is an elegiac quality to the story, particularly evoked through the descriptions of nature:

“For me that will always be the summer day of summers days – a cloudless sky, ditches and roadside deep in grass, poppies, cuckoo spit, trees heavy with leaf, orchards bulging over hedge briars. And we nimbled along through it”

Restoration, healing, judgement, the transitory nature of experience, time, life’s fragility… all these themes are explored in just 85 pages. And yet A Month in Country never seems limited or superficial. Absolutely deserving of its classic status.

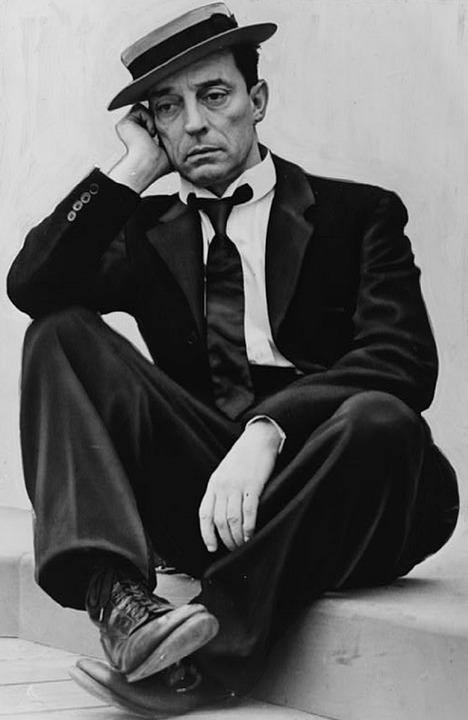

A Month in the Country was adapted into a film in 1987. I watched it after reading this and it is a broadly faithful adaptation but not entirely successful in capturing the sense of the summer, or the relationships between the characters. Definitely worth a watch though, with an excellent cast (especially Patrick Malahide as Reverend Keach):