Last week I watched When Corden Met Barlow, which had James Corden interviewing Gary Barlow. For those of you who don’t know these people, the former is a comedy writer and performer, the latter is a member of pop group Take That. When Take That split, Barlow was vilified in the press, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, as he seems an all-round good bloke. Take That have since reformed, and Gary Barlow is now proclaimed a national treasure by the very same press that tore him apart (update: see comments below for why this might have changed somewhat!) This got me thinking about how fame is constructed, and how it seems almost entirely arbitrary, not based on the person themselves but the image that is created, sometimes not even that. To this end, I thought I’d look this week at novels that feature a famous person as one of the characters.

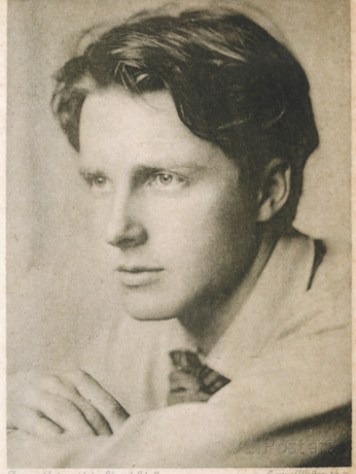

Firstly, The Great Lover by Jill Dawson (Sceptre, 2009), which concerns the poet Rupert Brooke. I went into this novel with some degree of trepidation because I think Brooke was a fairly mediocre poet, whose fame was elevated because he was posh, pretty and patriotic; exactly the type of person the establishment wanted to represent its lost youth in World War One.

(Image from: http://www.allposters.com/-sp/Rupert-Brooke-English-Writer-in-1913-Posters_i6856357_.htm )

Rather him than Wilfred Owen, who was middle-class, ordinary looking, gay, and whose verse took an uncompromising look at trench warfare. Of course, since then the quality of Owen’s poetry has seen his reputation far outstrip that of Brooke. But I will now climb down off my soapbox, and say that my concerns were unfounded, as this whole issue of image construction is precisely what Dawson is analysing in her novel. For example, with the rumour that Brooke fathered a child in Tahiti:

“perhaps people find it difficult to square the idea of the golden Apollo, the intellectual gentleman-soldier, finding peace not in an English meadow but on a tropical island far away.”

The novel is alternately narrated by Brooke and a maid where he boards in Granchester, the spunky and (mostly) wise Nell Golightly. In the present day, she is trying to convey the man she knew in a letter to the possible daughter of Brooke, who is now an elderly lady in Tahiti. In this way, Dawson draws attention to how biographies are as much about the biographers as their ostensible subject:

“I believe your mother wrote: “I get fat all the time.” Well, any woman would understand the meaning in that sentence. Unfortunately, your father’s biographers have all been men.”

The novel also shows the burden of fame, of being proclaimed “the handsomest young man in England” by WB Yeats. “I have the strongest feeling of foreboding. Something beyond my worst fears is about to happen […] And I think I know what it might be, but what I cannot tell is whether it is coming from inside my head or outside. Whatever it is, it is here at last. The construction, the Rupert Brooke, cannot hold me any longer.”

Through the first-person narrative, Dawson doesn’t give us a perfect golden-child Brooke, but the wholly subjective experience of a flawed, troubled man who is just so young, and given to unintentionally funny insights:

“The Great Lover, that’s me, not the beloved. The beloved is despicable. That’s the role of a girl.”

“I have resolved that Sodomy can only ever be for me a hobby, not a full-time occupation.”

This callow, aggrandising way could irritate some readers, but for me it just brought home how beyond all the image, Brooke was just a young man, as human as the rest of us, and how tragic it was that he and so many like him had their lives cut short: “the war was only the last eight months of his life, and yet that’s what he’s remembered for”.

What Dawson gives us through Nell’s voice is a fond but clear-eyed portrait of Brooke. “All that he was to me was gathered into that look I cast, but I don’t know if he saw it, or knew.” It made me feel that a well-researched (as this novel clearly is) fictional interpretation is probably just as valid as a “factual” biography.

“he was a difficult man to pin down, and he was in the habit of saying things playfully that he did not mean at all, or were quite the opposite of his meaning, so maybe it’s true that he was a little more of a slippery fish than some.”

So what are we left with? The answer is, the same as with any artist we admire: “Rupert’s true heart beats only on paper”. Their works are what speak most eloquently for them.

Secondly, someone who allegedly went skinny-dipping with Rupert Brooke, Virginia Woolf.

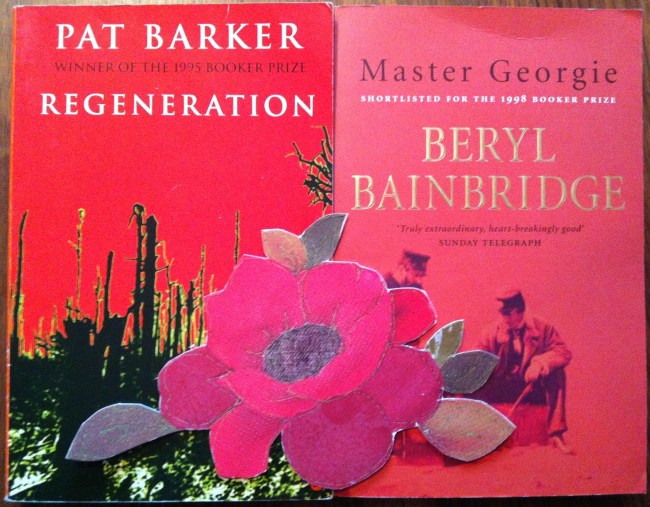

(Image from: http://www.4thestate.co.uk/?attachment_id=10089 )

The Hours by Michael Cunningham (4th Estate, 1999) is Pulitzer-winning novel which tells the story of three women linked by Woolf’s novel Mrs Dalloway.

One is Woolf herself, writing the novel in 1923; the others are Laura Brown, a housewife reading the novel in Los Angeles 1949; and Clarissa Vaughan, planning a party for a friend who calls her Mrs Dalloway, in New York at the end of twentieth century. The Hours is proof that a book doesn’t have to be long to be brilliant. At just 226 pages in my edition, it is so beautifully written that I had trouble pulling out individual quotes for this post. Each of the women lives a single day, both ordinary and extraordinary:

“Here is the brilliant spirit, the woman of sorrows, the woman of transcendent joys, who would rather be elsewhere, who has consented to perform simple and essentially foolish tasks, to examine tomatoes, to sit under a hairdryer because it is her art and her duty.”

Virginia Woolf’s fragile mental state is handled with great sensitivity, showing how she struggles to remain sane, and how the desires of those around her to keep her so may not be the best thing for her life:

“She is better, she is safer, if she rests in Richmond; if she does not speak too much, write too much, feel too much; if she does not travel impetuously to London and walk through its streets; and yet she is dying this way, she is gently dying on a bed of roses.”

The novel brilliantly captures the small, transient moments that make up life, and how they can all add up to great meaning, whilst seeming to signify nothing:

““You can’t possibly have too many roses” Clarissa says.

Sally hands the flowers to her and for a moment they are both simply and entirely happy. They are present, right now, and they have managed, somehow, over the course of eighteen years, to continue loving each other. It is enough. At this moment, it is enough.”

Astonishingly, the echoes across the three women’s lives from Mrs Dalloway and between each other never feels contrived. It is a brilliant evocation of lives led more or less quietly, and each character is strongly drawn enough to stand alone as well as alongside the other two.

I loved The Hours. The individual plots were well-paced, sensitive and insightful, in a style that used language delicately but was never pretentious. Highly recommended.

A film was made of The Hours in 2002. It’s quite good if you can get past the distraction of Nicole Kidman’s prosthetic nose (it took me a while):