Today is National Poetry Day, and the theme is Water. I’ve chosen two contemporary poets who wrote on this theme (one poem and one collection of poems). Mainly because I really like both the poets and they were who immediately sprang to mind, and also because I felt a bit bad about getting all Renaissance on your asses in my previous post. Twentieth/twenty-first century language only this week, I promise!

Firstly, “Swimming to the Water Table”, from Neil Rollinson’s first collection A Spillage of Mercury (Cape Poetry, 1996). Rollinson is famed for his unashamedly sexual poetry, but the theme of this poem couldn’t be more different. “Swimming to the Water Table” deals with the modern day echoes of the Moors Murders. I’m not sure how well-known these brutal, tragic events are outside Britain, so if you don’t know, there’s a link to the Wikipedia page here. This is not a pleasant subject matter, but I think Rollinson treats it with sensitivity. If you’d rather not approach such things, do give it a miss and scroll down to my second choice of poems. The poem begins:

“After hours of silence and the velvet

of peat cloughs, the road

from Manchester cuts the moor

like an act of violence.”

I think this is hugely clever. Rollinson is not going to write about the murders themselves – that would be hideous and entirely inappropriate. Instead he creates the bleak, eerie atmosphere on the moor where the children are buried, and a sense of attack. The noise of the main road, the assault on the person and senses, the sudden impact of it, manages to evoke the violence without in any way glamorising it. The sound of the language, with the hard ‘c’ of “cuts” and “acts” creates for the reader the same sense of jolting into harshness that the speaker has experienced with the road, as we are forced away from the softness of “velvet” and “peat”.

The speaker is told where he is and reminded of what has taken place there:

“…I can picture

the gaunt, blonde murderess, smoking

a cigarette, watching the road,

Brady unrolling the carpets, cracking

puns with every strike of the spade.”

Again, I think Rollinson is so skilled here at evoking without explicitly detailing: the shocking indifference of Hindley as she smokes and watches elsewhere, the “cracking” and “striking” of Brady, enactor of the most sickening violence imaginable. Rollinson is not shying away from what they did, and the verbs in this passage do not allow the reader to shy away either. At the same time, we’re not in the midst of the brutal acts themselves; this is all we need, gory details would be sensationalist and intrusive.

So where is the water? In these final lines:

“…The bleached

rib of an animal curls from the ground

like the heart of a flayed orchid.

Under my feet, the bodies of children

swim to the clear, sweet water table.”

I find this ending incredibly powerful. The animal rib shows the death that surrounds the moor, and a strange beauty that exists in the place – a flayed orchid is such an oddly violent, unsettling image. The idea of the bodies in the water table is both haunting and deeply upsetting, but at the same time, by having them swimming, not floating, the children are granted an independent agency. I think Rollinson uses the water imagery to reclaim for the children something they were denied in life: a final peace and tranquillity.

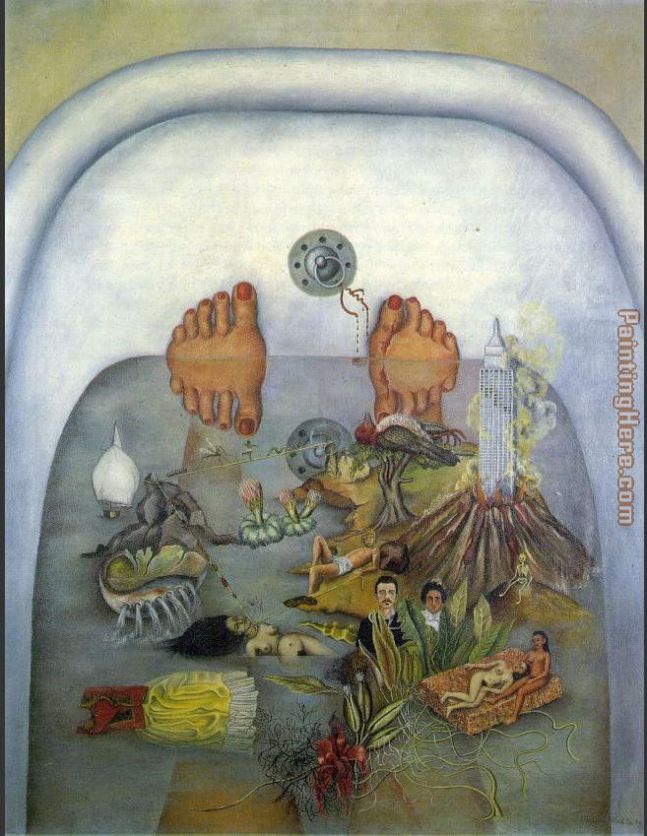

Secondly, a whole collection with a recurring theme of water, What the Water Gave Me: Poems After Frida Kahlo by Pascale Petit (Seren Books, 2010). For this collection, Petit took on the voice of the artist Frida Kahlo, and created poems around her paintings. There are six poems throughout the collection named “What the Water Gave Me”. The painting by Kahlo of this title looks like this:

(Image from: http://www.paintinghere.org/painting/what_the_water_gave_me-7293.html)

In “What the Water Gave Me IV” Petit layers image upon image to capture the multitude of scenes in the picture; it is 34 lines long but only one sentence. It begins:

“The bath I lie in like a sarcophagus,

the water that’s about to become kerosene

the surface I have to keep absolutely still

so my body can slip through it

like a reflection passing out of a mirror”

You can have a look at the picture and see what you think Petit is doing here, I don’t want to kill the poem by insisting the meaning I see is absolute. But I will say I think she captures the surrealism of Kahlo’s pictures with the notion of kerosene and the escaping reflection, and the odd, visceral yet detached relationship Kahlo has with her body. The kerosene also moves towards the underlying violence in Kahlo’s work. When she was 18 Kahlo had a severe accident when she was travelling on a bus. The severity of her injuries left her in agonising pain her entire life:

“the ulcers and craters, the giant

one- legged quetzal pierced by a tree,

my toes and their doubles, their blood-red nails,

the ex-votos to give thanks for surviving

twenty-two fractures, the miniature parents

on their atoll far off as my thigh,

the Empire State Building spewing gangrene

over my shin, that no perfume can mask

so no-one will visit

the life led dying”

I think Petit does a great job of capturing one form in another here, giving words to visual art. The shortening of the last two lines creates an emphasis to demonstrate the impact on the person of all the extreme imagery, and I think they are lines of real pathos. The layering of image upon image without a break creates a momentum that drives towards the final line:

“a steel handrail breaks off and hurtles towards me.”

This effectively evokes how for Kahlo, the accident is lived over and over, forever in the present tense. Its repercussions sent ripples through her entire life, and the impact of that steel handrail was devastating: it pierced through her abdomen and womb, meaning that although she wanted children, she could never carry one full term. As she lies in the bath, as she lives her life, she lives the accident.

You can read some more examples of the poetry in the collection on Petit’s website, here.

Well, this wasn’t the most cheery subject matter, but I think both the poets are huge talents and their poetry is really powerful, so I hope this post wasn’t too depressing! Do check out their other poems/collections, they’re well worth a look.

Here are the poems with a glass of water (sorry to be so prosaic, but hey, it represents the theme, right?)

Wow, this was a formidable post. Such great poetry!

LikeLike

I’m really glad you liked it, I think these poets are amazing! Thanks so much for the reblog as well.

LikeLike

I’ve been longing to read more poetry like that, so keep them coming!:)

LikeLike

I’ll do my best!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on funlifequotes and commented:

Wonderful

LikeLike

BRILLIANT post. I’m a bit obsessed with water… and I especially like water in literature (in fact did a blog post about books that feature swimming http://booksaremyfavouriteandbest.wordpress.com/2013/04/29/swimming-deserves-a-good-book/ )

LikeLike

Thanks very much! I’ve checked out your post, really interesting choices, I will get reading! Water can be such a powerful image for writers, it was a great choice of theme for National Poetry Day.

LikeLike

Agree, it’s a terrific choice with so much scope – flood, drought, swimming, drinking, reflection, oceans, lakes, rains… My obsession with water saw me become a swimming teacher in my teens (while my friends all had part-time jobs flipping burgers at Maccas), spend years rowing with various crews and eventually fulltime work in hydrology and river management. Obsessed…

LikeLike

Wow, that is obsessed! A very worthy obsession though – you must have been a lot healthier than all your friends at Maccas. I’m 5’10” which means I am stalked by the women’s rowing team at uni trying to get me to join, but the 5am starts seriously put me off!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post – thanks for pointing out the connection….

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Ha! I bet you were stalked by the rowers! After years of early starts for swimming and rowing, I’m an early riser now!

LikeLike

If only I could say the same….

LikeLike