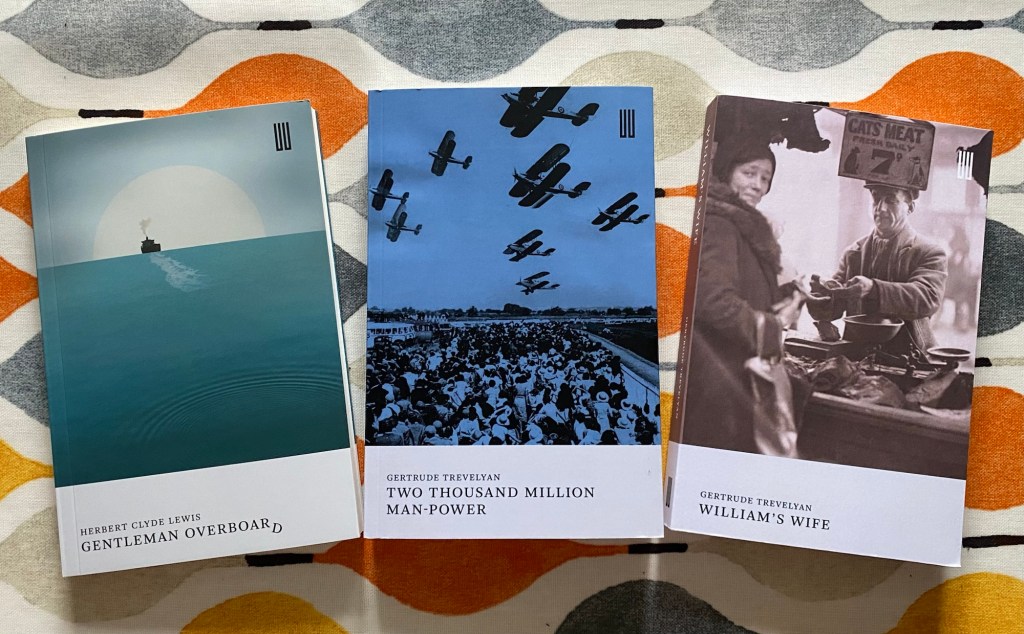

For this final week of Kaggsy and Lizzy’s brilliant #ReadIndies event, I’m focusing on three books from Boiler House Press, and their Recovered Books series edited by Brad Bigelow, founder of www.neglectedbooks.com, which brings “forgotten and often difficult to find books back into print for a new generation to enjoy.”

Five years ago, I read Wish Her Safe at Home by Stephen Benatar and it’s a novel that really stayed with me. The portrait of an isolated woman’s descent into serious mental illness, told from her own perspective, was deeply unsettling. I was put very much in mind of it when reading William’s Wife by Gertrude Trevelyan (1938).

At the start of the novel Jane is in her twenties and marrying the older, widowed Mr William Chirp, a local business owner.

“Jane had worked for her money, she knew the value of it. Knew how to save, and knew how to spend, too. All good quality, all of the very best. Mr Chirp might have done worse for a manager.”

But this is near the turn of the last century, and women are not managers of shops, they are managers of homes which are not as easy to leave. Jane is not a pleasant manager; she is quick to judge her maids and condescending, such as this early interaction over a fire:

“‘Why isn’t it laid,’ she asked haughtily, ‘this time of year?’ All alike.

‘The master wouldn’t never have it laid, not unless someone come. Will I lay it now, mum?’

Jane turned round sharply. ‘And quite right too. Wasting coal. No, certainly not.’”

Jane soon learns that it doesn’t matter if she knows how to spend on quality items, her husband will not have her spending at all. He is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. His want of generosity is spiritual as well as financial: he has no hobbies, no interests and no friends. His inability to value anything beyond material wealth accumulation for its own sake is brought into shocking focus during World War I:

“What the war was costing, that was what upset him. All those millions they wrote down in the papers. Though what was that to the government? The same as a few shillings to people like them. His face getting longer and longer, while he read about it. You’d think he was paying for it himself.”

Told in the third person from Jane’s perspective, the novel brilliantly builds the oppression of her marriage to this appalling person. Having Jane as not likable but still very sympathetic is a masterstroke by Trevelyan. It stops the tale becoming sentimental or easily dismissed as unrealistic. Instead, it is horribly believable.

The portrait of William is comical at times too, and this is finely judged. It doesn’t detract from the horror of Jane’s life with him at all. His reported speech is so minimal and trite as to be almost nonsensical. But his ridiculousness adds to the oppression: she is stuck with this man whose ignorance is so extensive as to make him absurd.

“At the end of April they stopped having the fire laid; the grate was filled in with crinkly blue paper in a fan. William sat with his feet in the fender and his hands, when he forgot, cupped over the paper fan.”

We see Jane scrabble to accumulate her own wealth through various small deceptions, necessary as her husband controls all her money and monitors it minutely. After he retires, William extends his miserliness to the time Jane spends away, commenting on the time whenever she returns from town. There is no physical violence in the marriage and no suggestion of what he will do if she takes longer than he thinks appropriate, but the control is absolute.

SPOILERS ahead: But further horrors await Jane when William dies. Her feelings of oppression do not dissipate, nor does her tight hold of money.

“It wasn’t until she found her money in the bag at the bottom of the basket and tipped it out carefully, with a cushion under, on the table, so that it shouldn’t chink, that she remembered William wasn’t about to hear it. It did seem queer, not having to be careful. Though it was all for the best, taking care; you never knew who might be about outside, listening to what was going on.”

She has taken on William’s prejudice, paranoia, and inability to spend. This escalates steadily, resulting in Jane moving several times and living in more and more straightened circumstances:

“She was so happy, having got away to herself, away from all that peeking and tittle-tattling, you wouldn’t believe. It wasn’t likely she was going to give away where she was, and have them all coming round again, like flies around a honeypot.”

This is heartbreaking – there is no ‘all’. She has no friends, has alienated her step-daughter, and is entirely alone. As she stops washing herself and her clothes, she is far from a honeypot for anyone. We are kept inside Jane’s unhappy mind, recognising far more than she does about her behaviour and how she is viewed by others.

William’s Wife is a novel that really gets under your skin. The oppression that Jane suffers, firstly through her marriage and then through a mind traumatised by all the years she has endured within that institution, is subtly evoked but relentless. It is a novel of great compassion written with such clear-sightedness that its power – eighty-six years later when women in the UK have far greater financial rights – remains undeniable.