I enjoy a golden age mystery at Christmas. It’s my comfort reading at any time of year, but I always try and read one at Christmas, when the tropes of being snowed in (and what will the thaw reveal?!), country houses, groups of people with various tensions trapped together, jovial facades and traditions hiding mendacity and murderers, work especially well.

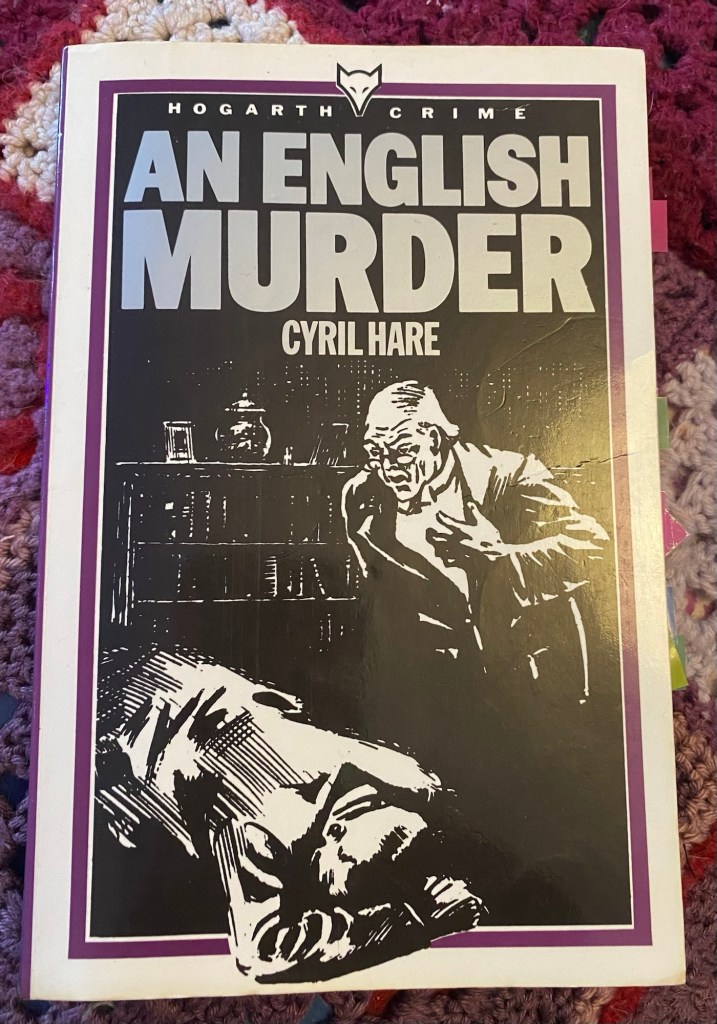

Unfortunately I had a couple of false starts. The first two I tried promised much of the above, but for various reasons didn’t quite work. Thankfully, a recent addition to the TBR, Cyril Hare’s An English Murder (1951), came to the rescue.

The title of the mystery is very apt: Hare takes a humorous but incisive view of postwar English society, making his points without rancour. Published only six years after the war, perhaps too harsh a criticism would not have been well-received by a generation who went through horrors in service of country, but at the same time things were changing and Hare captures this well.

The story opens:

“Warbeck Hall is reputed to be the oldest inhabited house in Markshire. The muniment room in the north-eastern angle is probably its oldest part; it is certainly the coldest. Dr. Wenceslaus Bottwink, Ph.D. of Heidelberg, Hon.D.Litt. of Oxford, sometime Professor of Modern History in the University of Prague, corresponding member of half a dozen learned societies from Leyden to Chicago, felt the cold sink into his bones as he sat bowed over the pages of a pile of faded manuscripts, […] The real obstacle that was worrying him at the moment was the atrocious handwriting in which the third Viscount Warbeck had annotated the confidential letters written to him by Lord Bute during the first three years of the reign of George III. Those marginalia! Those crabbed, truncated interlineations! Dr. Bottwink had begun to feel a personal grievance against this eighteenth-century patrician.”

Dr Bottwink is a concentration camp survivor. He is learned and wise, and really wants to be left alone with his papers “in response to an instinct that drove him to seek refuge from the horrors and perplexities of the present in the only world that was entirely real to him.”

Unfortunately for him, he will be drawn into the Warbeck family’s Christmas, including having to deal with the revolting Robert, heir apparent:

“I don’t think I shall greatly enjoy sitting down at table with Mr. Robert Warbeck.”

“Sir?“

“Oh, now I have shocked you, Briggs, and I should not have done that. But you know who Mr. Robert is?”

“Of course I do, sir. His lordship’s son and heir.”

“I am not thinking of him in that capacity. Do you not know that he is the president of this affair that calls itself the League of Liberty and Justice?”

“I understand that to be the fact, sir.”

“The League of Liberty and Justice, Briggs,” said Dr. Bottwink very clearly and deliberately, “is a Fascist organization.”

“Is that so, sir?”

“You are not interested, Briggs?”

“I have never been greatly interested in politics, sir.”

“Oh, Briggs, Briggs,” said the historian, shaking his head in regretful admiration, “if you only knew how fortunate you were to be able to say just that!”

One of the drawbacks of golden age crime is that you often come across anti-Semitism. It was a relief to see Dr Bottwink quickly established as the reluctant detective, and Robert and his organisation given short shrift.

Also present in the house are Sir Julius, cousin to Lord Warbeck and Chancellor of the Exchequer in the new socialist government, whose budget is likely to mean Warbeck Hall will be sold; his Scotland Yard bodyguard, Rogers; Lady Camilla Prendergast (who for unfathomable reasons is attracted to Robert); Mrs. Carstairs, politically ambitious for her husband; Briggs the ancient retainer steeped in duty to the class system and struggling with all changes; and his daughter Susan. I have a terrible memory with too many characters in mystery novels and this number was just right – enough for various suspects but not so many that I had trouble keeping them straight.

Hare lightens the story with gentle humour. Dr Bottwink’s outsider status means there are plenty of digs at English social mores, as well as direct from the authorial voice too, such as this sickbed reunion between Lord Warbeck and Robert:

“When they met they shook hands as English people should. But there is something rather absurd about shaking hands with a man who is lying down. Eventually he compromised by placing one hand lightly on his father’s shoulder.

“Sit down over there,” said Lord Warbeck gruffly, as though a little ashamed at his son’s display of emotion.”

I also enjoyed Rogers’ resolute imperturbability in the face of any heightened emotions from his political employer. Mrs Carstairs provides broader humour through unstintingly loquacious self-interest:

““She overran [Lord Warbeck’s library] like an occupying army, distributing her fire right and left and reducing the inhabitants to a stunned quiescence.”

If you’ve struggled with the social demands of Christmas dragging you away from your reading, you will certainly identify with Dr Bottwink. Far away from his beloved manuscripts, his considered, intelligent attempts at small talk fail miserably in the face of English ignorance:

Camilla laughed. “That was very simple of you, Dr. Bottwink,” she said. “Did you really expect a Cabinet Minister to know the first thing about constitutional history? He’s much too busy running his department to bother about a thing like that.”

“I fear that my knowledge of England is still imperfect,” said the historian mildly. “On the Continent it used not to be uncommon to find professors of history in Cabinet posts.””

On the first night Robert gets horribly drunk and offends even those more favourably disposed towards him. Dr Bottwink’s assessment of him remains unchanged:

“A disregarded spectator in the shadows, Dr. Bottwink gazed at him with cold and steady dislike, remembering other men who had professed principles not so very different from those of the League of Liberty and Justice, who had been noisy and genial in their cups, and had thereafter committed crimes beyond all reckoning.”

Unsurprisingly someone soon bumps Robert off with cyanide in his drink. But as it snows steadily, cutting everyone off, are the others safe? Will Dr Bottwink find the culprit in time, and if he does will anyone listen to him?

An English Murder was well-paced and a quick read. I hadn’t read Cyril Hare before but on the strength of this I’d be keen to read more. The Guardian included An English Murder in its Top Ten golden age detective novels and I can see why.

“When I am told that I cannot possibly think anything, my nature is so contradictory that I immediately begin to think about it.”

To end, Dr Bottwink’s knowledge of William Pitt helps him solve the mystery. He may take issue with the historical accuracy this portrayal: