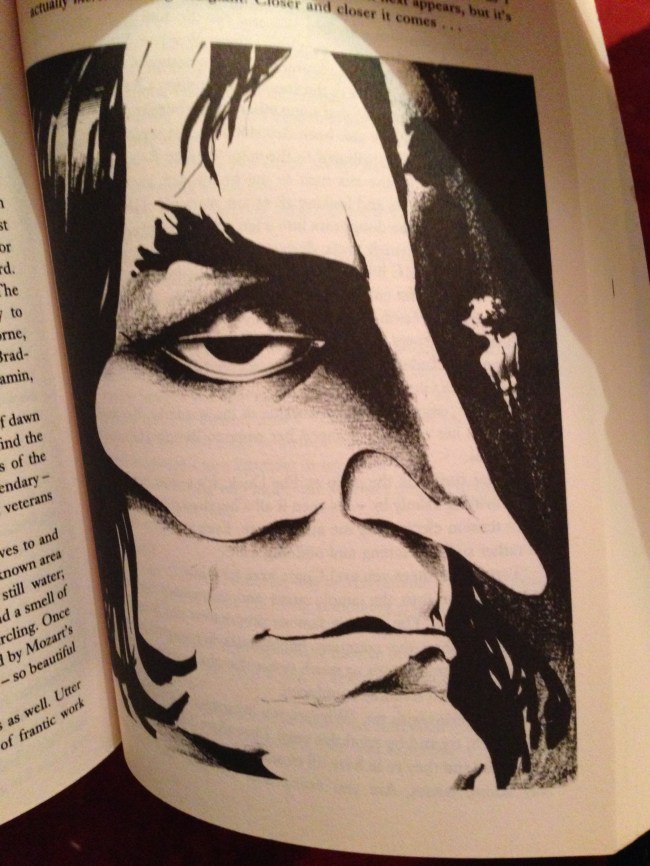

I’m in Oxford at the moment, a city I love. I thought I would look this week at novels set in Oxford, and although there are lots to choose from (I guess lots of writers chose to evoke their alma mater) I’ve picked two crime novels, as Oxford seems to encourage this type of story. I’m not sure why this occurs, but maybe it’s because it’s seen as such a respectable institution and it’s fun to think of a seething mass of violence and intrigue below the calm façade. Here’s a picture of Oxford’s most famous fictional detective, to compensate for the fact that I’m not looking at any Colin Dexter novels:

Firstly, The Case of the Gilded Fly by Edmund Crispin. This was the first in a series of novels featuring the sleuthing Oxford don Gervase Fen, and is from the Golden Age of Detective fiction, written in 1944. The opening paragraph struck a chord with me:

“To the unwary traveller, Didcot signifies the imminence of his arrival at Oxford; to the more experienced, another half-hour at least of frustration. And travellers in general are divided into these two classes; the first apologetically haul down their luggage from the racks on to the seats, where it remains until the end of the journey, an encumbrance and a mass of sharp, unexpected edges; the second continue to stare gloomily out of the window at the woods and fields into which, by some witless godling, the station has been inexplicably dumped”

Well, the woods and fields may be much less evident, but otherwise… seventy years on and nothing changes. Travelling on this train are Gervase Fen, his friend Sir Richard Freeman who is Chief Constable of Oxfordshire and wishes he was a don (while Fen wishes he was police officer) and various members of a drama group, who will return to London with their numbers somewhat diminished. Fen is a likeable, eccentric don, whose “normal overplus of energy …led him to undertake all manner of commitments and then gloomily to complain that he was overburdened with work and that nobody seemed to care”; he distracts himself on the train by wishing for “’A crime! …A really splendidly complicated crime!’ And he began to invent imaginary crimes and solve them with unbelievable rapidity.”

The first murder, of uber-bitch Yseult Haskell, takes place in a room in college close to Fen’s office, and so much to his delight he is distracted from his work on minor eighteenth-century satirists to investigate:

“His usually slightly fantastic naivety had completely disappeared, and its place was taken by a rather formidable , ice-cold concentration. Sir Richard, who knew the signs, looked up from his conference with the Inspector and sighed. At the opening of the investigation, the mood was invariable, as always when Fen was concentrating particularly hard; when he was not interested in what was going on, he relapsed into a particularly irritating form of boisterous gaiety; when he had discovered anything of importance he quickly became melancholy […] and when an investigation was finally concluded, he became sunk in such a state of profound gloom it was days before he could be aroused from it. Moreover these perverse and chameleon-like habits tended not unnaturally to get on people’s nerves.”

I’m not going to say too much about the plot as its nearly impossible not to give spoilers. But if you think the eccentric Fen is someone you’d like to spend time with do look at The Case of the Gilded Fly. I loved the dry, yet gentle humour in the writing, and it was a well-paced, easy read. My favourite character however, was one of the minor players; unlike a lot of detectives, Fen does not have a complicated romantic life filled with encounters with unsuitable lovers, but is married to the brilliantly indulgent Mrs Fen:

“After she had greeted the Inspector with a slow, pleasant smile, Fen seized up the gun and handed it to her, saying:

‘Dolly, would you mind committing suicide for a moment?’

‘Certainly,’ Mrs Fen remained unperturbed at this alarming request, and took the gun in her right hand, with her forefinger on the trigger; then she pointed it at her right temple.

‘There!’ said Fen triumphantly.

‘Shall I pull the trigger?’ asked Mrs Fen.

‘By all means,’ he said absently, but Sir Richard surged up from his chair crying hoarsely: ‘Don’t! It’s loaded!’ and snatched the gun away from her. She smiled at him. ‘Thank you, Sir Richard,” she said benignly, ‘but Gervase is hopelessly forgetful, and I shouldn’t have dreamed of doing such a thing. Is that all I can do for you gentlemen?’”

What a woman. Next, a much more recent tale (2005) whose title tells you exactly what to expect: The Oxford Murders by Guillermo Martinez (trans. Sonia Soto). The novel is narrated by a postgraduate mathematics student, who shortly after arriving in England finds his landlady murdered, discovering the body at the same time as his hero, Professor Arthur Seldom “a rare case of mathematical genius”. The Professor is there because he received a note telling him that something would happen “the first of the series” followed with a mathematical symbol, a circle. As more people die, Seldom continues to receive notes ending with symbols, and believes the murderer is taunting him specifically as he wrote a book on mathematics where he argues that “except in crime novels and films, the logic behind serial murders…is generally very rudimentary…the patterns are very crude, typified by monotony, repetition, and the overwhelming majority are based on some traumatic experience or childhood fixation”. Some serial killers may take that as a challenge…

The two start working together, using their academic approaches to try and decipher the logic of the murders. There’s a lot of maths talk, but it’s not overwhelming even for someone like me whose dealings with numbers is limited entirely to their monthly budget. The combination works well and doesn’t feel forced:

“There is a theoretical parallel between mathematics and criminology; as Inspector Petersen said, we both make conjectures. But when you set out a hypothesis about the real world, you inevitably introduce an irreversible element of action, which always has consequences.”

Can they make their hypotheses apply in the real world and solve the symbolic series in time to prevent more murders? What do the symbols really represent? The Oxford Murders is a short novel and not particularly complex despite the setting in elite mathematics; it’s well written but if you’re a crime aficionado you may find it a bit too straightforward.

The Oxford Murders was made into a film a few years back; from this trailer I would say it’s a fairly faithful adaptation:

Here’s my attempt at a vaguely mathematical end: from the shaded area of a Venn diagram of Oxford and books, here is a picture of one of the most beautiful libraries you’ll ever see – the Radcliffe Camera in central Oxford. The picture’s wonky because it was blowing a gale and I was up the top of the tower of St Mary the Virgin, where the wind was so strong I thought I, or at the very least my phone, was about to get whipped off the viewing balcony into the square below. Thankfully we both made it back intact.