I write to you from within a fog of lemsip and cough syrup. Yes, this week I’ve had a grotty cold. Nothing major by any means, but just enough to make me feel grim and make the days a little greyer. So I thought for this post I’d cheer myself up and be totally self-indulgent, by choosing two books that are thematically linked only in the fact that they are two of my favourites.

Firstly, If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things by Jon McGregor (Bloomsbury, 2002). This was McGregor’s first novel, longlisted for the Booker, and written when he was only twenty-six. Choking down my jealousy, I am able to tell you that the accolades are highly deserved. I think this is such a beautifully written, confident debut. It tells the story of an ordinary street and its ordinary inhabitants, over the course of a day.

“The short girl with the painted toenails, next door, she says oh but did you see that guy on the balcony, he was nice, no he was special and she savours the word like a strawberry, you know she says, the one on the balcony, the one who was speeding and kept leaning right over, and they all know exactly who she means, he’s in the same place most weeks, pounding out the rhythm like a panelbeater, fists crashing down into the air, sweat splashing from his polished head.”

“In his kitchen, the old man measures out the tea-leaves, drops them into the pot, fills it with boiling water. He sets out a tray, two cups, two saucers, a small jug of milk, a small pot of sugar, two teaspoons. He breathes heavily as his hands struggle up to the high cupboards, fluttering like the wings of a caged bird.”

“She opens her front door, just a little, just enough, and she hops down her front steps, the young girl from number nineteen, glad to be out of the house and away from the noise of her brothers. The television was boring and strange anyway, it was all people talking and she didn’t understand. She taps her feet on the pavement, listening to the sound her shiny black shoes make against the stone…”

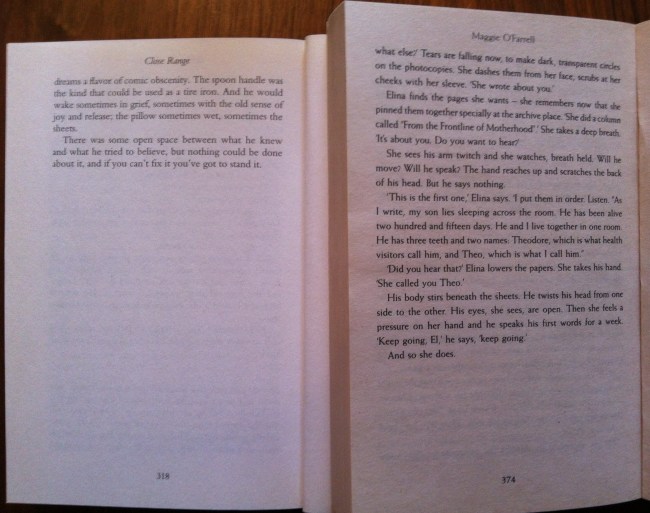

I hope these three examples give a good idea of why I love this novel so much. McGregor is so skilled at finding the poetry in ordinary lives and how the self is expressed through seemingly innocuous actions. Gradually the inhabitants of the street emerge as fully realised characters from the details of this one day. This narrative is intertwined with a first person narrative, and you begin to realise that something significant, and tragic, took place on this ordinary day. If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things is a novel of startling sensitivity and lyricism.

If this has whetted your appetite for McGregor’s novels, I discuss his second novel, So Many Ways to Begin here.

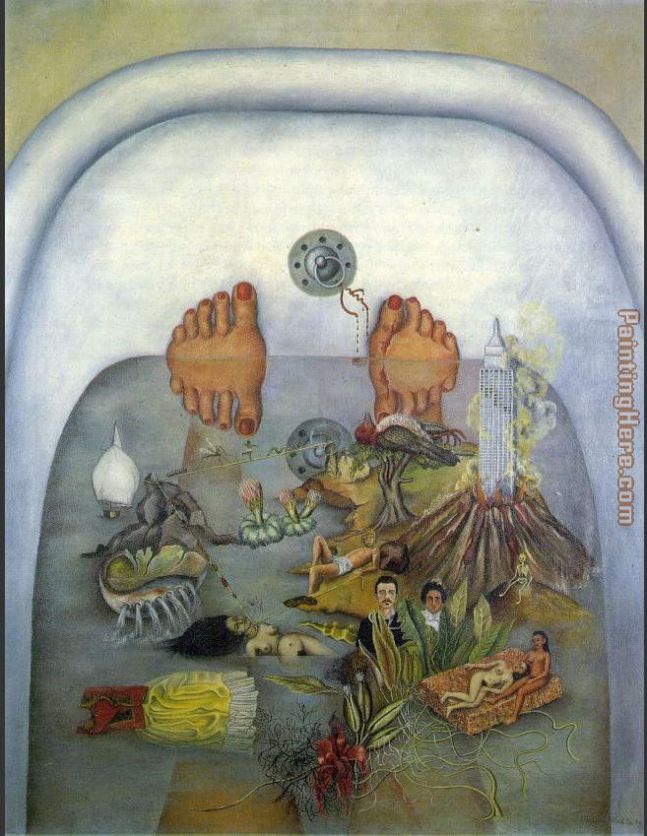

Secondly, Death and the Penguin by Andrey Kurkov trans. George Bird (1996, English translation 2001, Harvill Press). How to describe this novel? It’s frankly a bit bonkers and one of those I think I understand, but maybe it’s about something else entirely. It’s a great read though. It tells the story of Viktor, an aspiring writer who gets a job writing obituaries, and his pet penguin Misha, who he took on when Kiev zoo gave all its animals away: “he had been feeling lonely. But Misha brought his own kind of loneliness, and the result was now two complimentary lonelinesses, creating an impression more of interdependence than amity.”

The character of this depressed penguin is as vividly realised as any of the human characters, and you really start to feel for this bird who symbolises the existential crisis of his owner and others caught up in a post-Soviet world that they do not understand: “Sleeping lightly that night, Viktor heard an insomniac Misha roaming the flat, leaving doors open, occasionally stopping and heaving a deep sigh, like an old man weary of both life and himself.”

The fragile relationship between Viktor and Misha is tested to its limit by a series of surreal events. Viktor’s friend Misha-Non-Penguin leaves his daughter Sonya with Viktor, and so he drifts into a family unit with this self-contained little girl and her nanny. But meanwhile, someone is using his obituaries as a hit-list, and he is being followed by a mysterious stranger known only as the fat man…

“The Chief considered him through narrowed eyes.

“Your interest lies in not asking questions,” he said quietly. But bear in mind this: the minute you’re told what the point of your work is, you’re dead. […] He smiled a sad smile. “Still, I do, in fact, wish you well. Believe me.””

Death and the Penguin is a surreal adventure story, a post-Soviet satire, an examination of the individual spirit up against forces that seek to control. It’s funny and it’s sad, it has something to say, and it says it in a truly unique and engaging way.

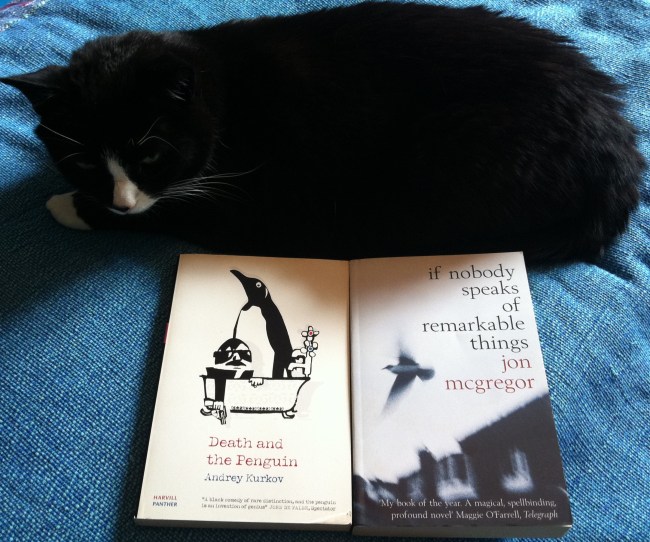

Here are the novels with another of my favourite things, my psychotic cat (he looks calm in this photo, but trust me, he is hell-bent on world domination):