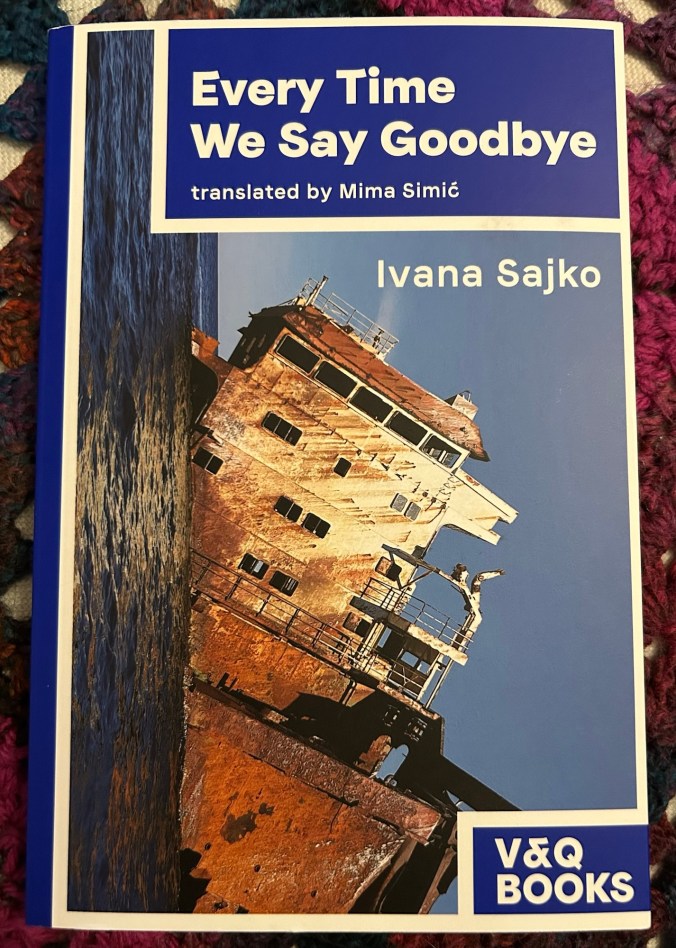

I don’t get many books sent to me by publishers, but I was really pleased to be offered Every Time We Say Goodbye from V&Q Books who specialise in writing from Germany. Ivana Sajko was born in Zagreb and her translator Mima Simić is Croatian, they both now live in Berlin. Back in 2023 I read Love Story from the same author, translator and publisher and found it powerful and unflinching.

With everything that’s been going on for me with work it’s taken me some time to get to it, but at 118 pages it’s a perfect Novellas in November read, hosted by Cathy and Bookish Beck.

A writer leaves his partner to catch a train from south-east Europe through to Berlin.

“Leaving nothing behind but the story of a man travelling through Europe hit by another crisis, boarding a train convinced that it doesn’t really matter why he’s leaving, as he has no reason to stay, the story of a man sinking into his notebook, grasping mid-descent at his messy notes, each of them opening a new abyss beckoning another fall, a man who still cannot bring himself to open the flat box of photographs from his mother’s drawer,”

Each short chapter is a single sentence, and while I know this sounds off-putting, I thought it worked brilliantly. The long, weaving sentences broken by commas perfectly captured the sense of memories surfacing back and forth against the physical rhythm of the train journey.

The narrator is not particularly likable but he is recognisable and believable. As he considers how his relationship failed and looks back on his life so far, his experiences are inextricably bound to the time and geography he lives within.

“Everyone left because they had to: my mother, my father, my brother, and all these goodbyes weren’t dramatic gestures but quiet moments of stepping onto a train or a bus, followed by long rides in uncomfortable seats with stiff legs, full bladders, a restless heart and the anticipation of the final stop, which meant a new beginning and facing expectations”

Twenty-first century Europe is shown as a place of dislocation, whether through wars, socio-economic pressures, or pandemics. The impossibility of the personal and political being distinct from one another is variously explored. The writer’s depression is at least partly due to what he witnessed as a journalist:

“I lay on the ground at Tovarnik station amid garbage and people now grown in distinguishable, on the filthy platform strewn with large stones, under the European Union flag that flapped ironically next to a border crossing sign that read ‘Croatia’ and ‘EU’”

And I particularly liked this observation about how international covid restrictions made explicit the shortcomings in his and his mother’s relationship:

“The plague was our internal standard, and now that it had also driven the rest of the world apart, our few metres gap became the global standard, the plague revealed the fatality of the smallest gestures and the significance of shortest distances, a single step towards or away from a person could help or harm them; gestures we’d used to hurt each other suddenly became protective, so we didn’t really need to make an effort to adopt the new regulations”

Grounded as it is the events and establishments of the day, Every Time We Say Goodbye still remains a slippery narrative, questioning the subjectivity and reliability of memory and how we understand our experiences:

“I’d like to write about him making faces and winking at me across the table, but none of that is true, I remember none of it, my brother has no face at all, he has no smile, no voice, no drops of sweat glisten on his skin, no scabs on his knees, he has no clear outline, there are no concrete details to him, every time I look in his direction, all I can see is a murky silhouette of a boy, he’s too far away”

There is a lot packed into this slim novella. It is undoubtedly a commentary on contemporary Europe; but it also portrays the inadequacy of human communication and understanding, and how this can wreak damage in our closest and most intimate relationships. Trauma is visited on large and small scales.

Not an easy read, but one I am glad to have read for its brave choices in style and subject matter. If, like me, you enjoy a Translator’s Note, there is a really interesting one from Mima Simić included.

To end, of course I was going to go with the obvious choice, an absolute classic: