When I was searching for quotes about libraries I really liked this quote by Libba Bray but it was too long to use for a title:

“The library card is a passport to wonders and miracles, glimpses into other lives, religions, experiences, the hopes and dreams and strivings of ALL human beings, and it is this passport that opens our eyes and hearts to the world beyond our front doors, that is one of our best hopes against tyranny, xenophobia, hopelessness, despair, anarchy, and ignorance.”

This week’s theme is libraries, because one of the unforeseen benefits of my 2018 book buying ban is that I have rediscovered the joy of the library. You may well be wondering what kind of moron I am not to foresee this, but I really didn’t. The purpose of the book-buying ban is to get through the piles of unread books I own. It’s working, but not quite as well as I hoped because I’ve realised my library has novels. Up until this point I’d mainly used it for non-fiction books. It’s taken the ban for me to realise I can get in the library queue for new releases and get hold of rare books I’ll never be able to afford. Libraries are amazing!

Firstly, I finally reached the top of the queue for Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor, which was published before my book buying ban last year, but I hadn’t got a copy. McGregor is one of my favourite authors and I didn’t want to wait another year before reading this, so I got on a long waiting list at the library.

Disclaimer: McGregor is never going to get anything but gushing reviews from me. I’ve loved his writing since his first novel If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things and as far as I’m concerned he can do no wrong. I understand this novel has divided people and I think its because the premise sets up certain expectations. A 13 year old girl, Becky Shaw, disappears from a village where she and her parents are holidaying for new year. However, this isn’t a thriller. It isn’t about the search for the girl, or what happened to her, or who may have taken her. What it is about is a community, the people in it, how their stories touch on one another. If like me, you’re a fan of McGregor, this won’t greatly surprise you. Although the rural setting is unusual for him, the themes are not. But if you come to it expecting a missing person puzzle to be solved, you’ll be sorely disappointed.

There are many recurring phrases and details in the book. Becky is 13, the village has 13 reservoirs, the story is set over 13 years and divided into 13 chapters. The chapters begin “At midnight when the year turned…” At intervals we are reminded “The missing girl’s name was Rebecca, or Becky, or Bex”. The effect is to show how things move on within the familiar; village lives continue but they also change. Meanwhile, Rebecca/Becky/Bex is held in a stasis, forever 13, the questions around what happened to her left hanging.

I associate McGregor with urban settings, but he writes beautifully of rural life. Old traditions are dying out: only one of the residents bothers collecting nettles for tea or elderflowers for cordial. The butchers – like so many local shops – closes due to lack of demand. Yet the seasons in their distinct beauty are there:

“On Bonfire Night there was a heavy fog, thick with woodsmoke, the fireworks seen briefly like camera flashes overhead. In the beech wood the foxes prepared their dens. The vixens dug down into old earths and reclaimed them, lining them out with grasses and leaves. In the eaves of the church the bats settled plumply into hibernation. By the river the willows shook off the last of their leaves. At night the freight trains came more often a single white leading and the wagons shadowing heavily behind. The widower asked Clive for advice over pruning his fruit trees and Clive was surprised to see the state things were in.”

McGregor does this throughout the novel, going straight from describing the natural world into a detail about the lives of one of the villagers without a paragraph break. In doing so he weaves the lives into the world that surrounds them and shows how one cannot be understood without the other.

I thought Reservoir 13 was absolutely stunning. It reminded me of Virginia Woolf in the use of repeated phrases and the focus small but significant details. In his usual unshowy style, McGregor captures the beauty and fragility of everyday life.

After I finished Reservoir 13 I went straight to the library to see if they had a copy of Reservoir Tapes, the sequel of sorts, and I didn’t even have to put my name in the queue for it. Reservoir Tapes is a series of short stories connected to Reservoir 13, originally broadcast on the radio. You can listen to them here.

Secondly, I found my library had a copy of Rhododendron Pie, Margery Sharp’s first novel from 1930, which is practically impossible to find and which you pay hundreds of pounds for online. There was a copy just sitting there – I couldn’t believe I hadn’t checked before.

Image from here

Rhododendron Pie tells the story of Ann Laventie, whose natural leanings towards conservatism mark her out as different from the rest of her family. Her sister Elizabeth begins the birthday tradition of inedible floral birthday pies of the title, while little Ann would prefer an apple pie.

“It had once been said of Mr Laventie that he was a traditionalist in wine and a revolutionary in morals; and indeed, this capacity for making the best of both worlds was an outstanding characteristic of the family. They combined the extremes of old-world elegance and modern freedom, tempering a belief in free verse and free love with an equal feeling for societal decorum.”

As the children grow up, Elizabeth becomes an intellectual forever having essays published in journals while her brother Dick becomes a sculptor. Ann is at a bit of a loss. She is good at admiring what the others do and she is well-liked, but she flounders in working out what she wants and where she fits in. Sharp captures how society is changing for the interwar generation; one of Ann’s friends is perfectly open about the men she lives with on occasion. While there is discussion around this which seems remarkably forward-thinking and would sit well with readers today, Ann does not want a bohemian lifestyle.

“ ‘What I want,’ continued Ann recklessly, ‘is a nice wedding in the village church, with a white frock and orange blossom and lots of flowers and ‘The Voice that Breathed’ and two bridesmaids in cyclamen pink and rose petals afterwards and a reception in the drawing-room with a string quartet playing selections from Gilbert and Sullivan. In June. And a honeymoon in the Italian Lakes.

‘Where does Gilbert come in?’

‘He doesn’t. And I want to live in a house, not a flat, even if it’s only a little one in a suburb where there’s no-one amusing, with a back garden to dig in. And have bird pattern chintzes in the drawing-room and cold supper on Sundays because the maid’s out. I shall probably,’ finished Ann defiantly, ‘take a stall at the church bazaar.’”

Ann doesn’t come across as remotely priggish or boring though. She is authentic and truthful, and struggles with her knowing, arch, ironic family

“ ‘One of your family methods. Every now and then you do something deliberately ordinary, but in inverted commas so to speak, just to see what it feels like.”

What Rhododendron Pie is about is working out who you are and what you want from the world, and how tricky this can be when you seem to be at odds with your family and the section of society you live within. Without any didacticism, Sharp captures how this is especially hard for women. New freedoms are opening up, but women are still judged more harshly by society and have their actions further circumscribed by law.

“These were the things they understood, patient hope and quiet brave endurance: these were the woman’s part.”

Rhododendron Pie is remarkably accomplished for a first novel. Sharp would hone her skills further in future novels – particularly characterisation, which is a bit weak here – but her wit is here, her warmth, and her wisdom.

“‘That’s what you clever people never understand. You talk about life as though it were something rare and surprising that one had to be careful of. It’s nothing of the sort. It’s ordinary. And it’s only when you’ve accepted it as ordinary that you begin to see the wonder of it. That a swallow or a green field should be beautiful is nothing, but that they should be common as dirt is a miracle. I am continually amazed…at the casual beauty of things.’”

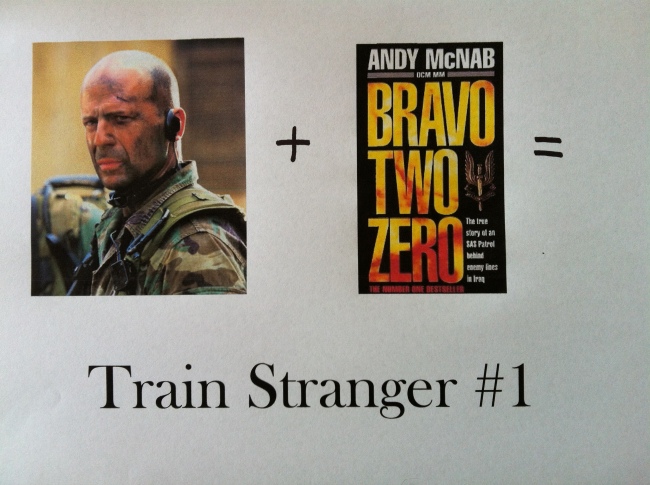

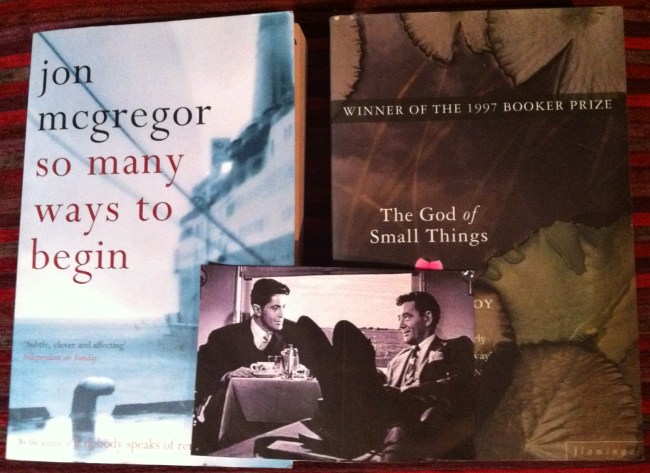

To end, a woman whose name helpfully rhymes with her profession, and an annoying man who won’t shut up and let people read in peace: