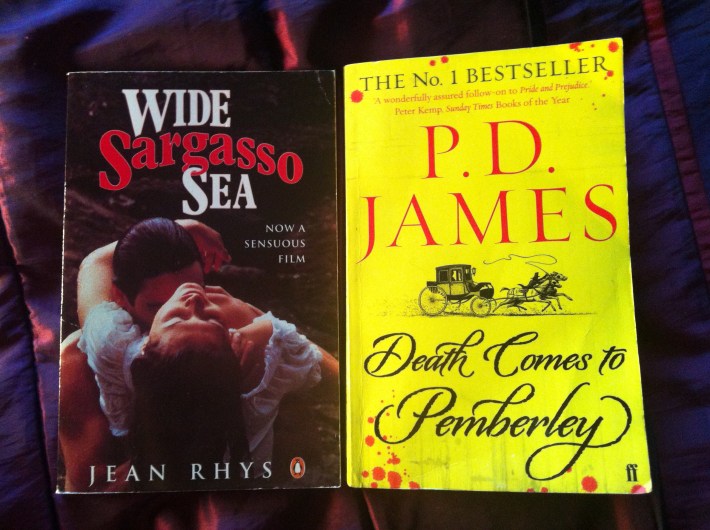

My lovely friend H feels I take life too seriously & this is reflected in my choice of reading matter. As such, she keeps lending me light reads in the hope that I’ll chill out & stop living my life like I’m a some sort of doomed Hardy heroine (which I dispute: I harbour no plans to start bedding down at Stonehenge. Far too cold, I prefer central heating. Probably just as well as they’ve restricted access to the monument now.) But because she is a good friend & I love her (and she’s probably right in general), I read the books she gives me. This week it was Death Comes to Pemberley by PD James (Faber & Faber, 2011), so I decided to write about it here, making the theme of the post prequels and sequels.

Death Comes to Pemberley is a sequel to Pride and Prejudice, set 6 years after the end of Austen’s novel, where Darcy & Elizabeth are happily married with 2 sons. I’m not a big crime reader, so I hadn’t read any PD James before, but I know crime aficionados who highly rate her. To me the crime element of this novel was its weakest link – the plot was very slight and there’s no detective work as such, the crime is solved as the murderer confesses. But I never wanted to blog about books in a critiquing way, so I’ll stop and look at what is to celebrate, as I planned. James has great fun with the concept of a sequel to Pride and Prejudice, with comments on the backstory like: “If this were fiction, could even the most brilliant novelist contrive to make credible so short a period in which pride had been subdued and prejudice overcome?” (Answer: Yes). She also explains potential problems in the original, like why Darcy’s first proposal and following letter were so rude (he was trying to make Elizabeth hate him so he wouldn’t have to deal with his attraction to her). Whether or not you like this explanation depends on how you’ve read the original, and while it’s a shame to pad out the room for interpretation which helps readers feel a sense of ownership over a novel, James is as entitled to her view as anyone else. She is obviously a huge fan of Austen and characters from Emma also make an appearance thorough a verbal report: a child is adopted by Mrs Harriet Martin nee Smith, friend of Mrs Knightley.

Part of modern scholarship on Austen is to look at what is hidden in her work: the slavery hinted at in Mansfield Park, for example. Writing from a 21st century perspective, James can make explicit certain factors like feminism and the Napoleonic War which readers today may pick up on but are only shadows in Austen’s works:

“We have entered the nineteenth century; we do not need to be a disciple of Mrs Wollstonecraft to feel that women should not be denied a voice in matters that concern them. It is some centuries since we accepted that a woman has a soul. Is it not time that we accepted that she also has a mind?”

“The war with France, declared the previous May, was already producing unrest and poverty; the cost of bread had risen and the harvest was poor. Darcy was much engaged in the relief of his tenants ..”

In this way James’ novel offers a chance to view well-known characters in more well-rounded way, taking into account their social and political circumstances in a wider perspective, beyond that of the Regency marriage market. However, and I realise this is an obvious point so I won’t linger on it, PD James is not Jane Austen, and as such the novel reads a bit flat. The effervescent wit is gone and there’s not really anything to replace it.

It was a brave decision that James made with Death Comes to Pemberley, as writing a sequel to Pride and Prejudice is really a thankless task. Austen and her characters are so greatly loved I doubt any author other than Austen herself could do them justice. While placing them in genre fiction like crime is probably a good idea so that its clear you’re working within conventions other than those of the original novel, I can’t help feeling that Death Comes to Pemberley may prove disappointing for both crime fans and Austen fans.

For the prequel part of this post I’ve chosen probably the most well-known of all prequels: Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966, my copy Penguin 1993). Wide Sargasso Sea looks at the events that occurred prior to Jane Eyre, and how Rochester’s first wife became the madwoman in the attic. Rochester marries the Creole heiress Antoinette Cosway in the Carribean. There is a strong sexual attraction between them as Rochester describes:

“Only the sun was there to keep us company. We shut him out. And why not? Very soon she was as eager for what’s called loving as I was – more lost and drowned afterwards.”

But this is not enough to cover the differences between them “It was all very brightly coloured, very strange, but it meant nothing to me. Nor did she, the girl I was to marry.” and the cracks in their marriage soon start to appear, with distrust, jealousy and violence on both sides. The result of this we already know…

What happens to Antoinette is a commentary on both men’s exertion of power over women, and the coloniser’s power over the colonised. Rhys takes the “other” of Jane Eyre and gives her a voice, placing us alongside Antoinette and showed how flawed and racist notions of “other” are. Rochester, the rich white Englishman, seeks to control Antoinette and does so by renaming her and confining her – the parallels with slavery are clear. As a woman, she is also subjugated by a society that is on Rochester’s side:

“When a man don’t love you, more you try, more he hate you, man like that…”

“I cannot go…I am not rich now, I have no money of my own at all, everything I had belongs to him…that is English law”

However, by giving the narrative voice to Rochester as well as Antoinette, Rhys ensures a balance to Wide Sargasso Sea that means you can’t write it off as limited perspective polemic. It has had a huge influence on how Jane Eyre is read, and I think this is because it is so sensitive and subtle a reading and portrayal of the characters. Rhys succeeds in creating a backstory that is wholly believable and recasts the frames of reference through which Jane Eyre is viewed, without ever undermining the original work. This can be seen in interpretations such as the BBC’s 2006 version of Jane Eyre which emphasised Bertha’s (as she is then named) sexuality, associated her with the colour red as in Wide Sargasso Sea, and had her played by the beautiful Claudia Coulter to make Rochester’s physical attraction to her easy to understand (the BBC also filmed a version of Wide Sargasso Sea the same year). The fact that Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s behemoth of feminist literary criticism took the title The Madwoman in the Attic (1979, Yale University Press) shows how the character of Bertha (and characters like her) are being reassessed, and I think it’s reasonable to assume Wide Sargasso Sea played no small part in that. Unlike Death Comes to Pemberley, Wide Sargasso Sea stands alone as a great novel, and simultaneously hugely enhances reading the source work. I recommend the latter unreservedly, and the former as a point of interest and a quick, throwaway read.

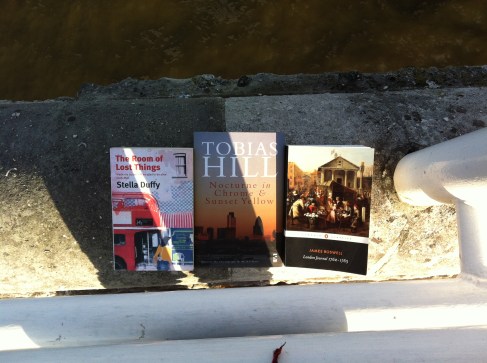

I was wondering how to photograph the books in a way that represented the theme, then as I looked at the covers I realised they sort of represented a before and after already – la petite mort followed, inevitably, by le grande mort. What a depressing note to end on – I think H has got her work cut out…….