In the words of Sir Noddy of Holder, “It’s ChristmAAAAAAAs!”

If you are already baulking at the thought of spending several days trapped together with your dearest loved ones, a selection tin of chocolates and a turkey that never seems to end despite the fact that everyone somnambulates around with its half-masticated flesh hanging from their mouths for at least twenty hours in every day, then take heart. Being trapped together in country houses has provided some wonderful material for Christmas reads, and escaping into one will prevent you killing off your relatives (which I wouldn’t recommend anyway, because you are, in crime-story parlance, part of a closed circle of suspects and you’ll definitely get found out).

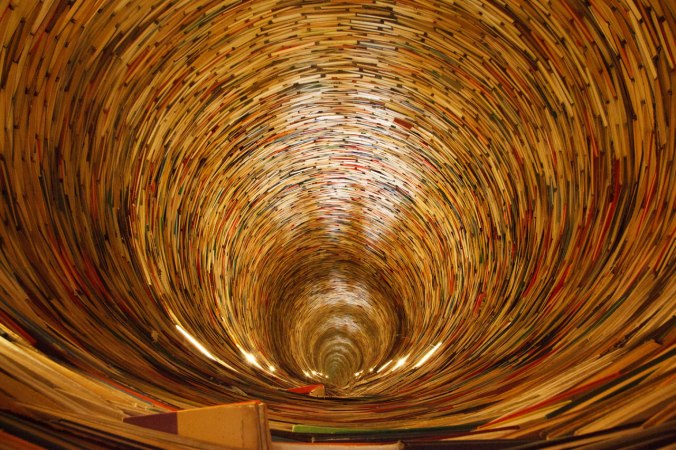

(Image from here)

Firstly, The Santa Klaus Murder by Mavis Doriel Hay (1936), a novel from the golden age of detective fiction which has been re-published by the British Library Crime Classics series. The Melbury family, despite their inherent distaste for one another, spend Christmas together at Flaxmere, the country seat of Sir Osmond Melbury. Sir Osmond is deeply unlikeable, a controlling patriarch who manipulates his family through threats of disinheritance. His daughter Jennifer attempts a certain degree of rebellion:

“She developed some sort of life of her own by working in the Women’s Institutes, but these activities were hampered by Sir Osmond, who disapproved of what he considered the Bolshevist tendencies of the movement.”

Of course, it’s no surprise to the reader that it is Sir Osmond who meets a sticky end, shot in the head by someone clearly undertaking a Yuletide charitable act for the benefit of his family. Suspicion falls on the guest dressed in the Santa costume (definitely not the actual Santa, kids, don’t worry)who discovered the body. Colonel Halstock, Chief Constable of Haulmshire and friend of the family, is brought into investigate. The realisation that in fact there were two people wandering around in Santa outfits is brought to the Colonel’s attention:

“there was a tap at the door and in walked Miss Portisham and George’s son, Kit. The child strutted in, very pleased with himself, and yet a little nervous. I couldn’t think for a moment what made him look so absurd. Of course, it was the eyebrows! He had tufts of bushy white hair stuck onto his brows, rather crookedly, one of them taking a satirical tilt towards his temple.”

This being a golden age novel there are false wills, documents half-burnt and discovered in fireplaces, faithful old retainers speaking in regional accents, and a thwarted young couple. The Christmas setting is perfect for a country house murder:

“they must be having a pretty awful time, I realized, especially as they were, most of them, not given to intellectual occupations. They were forbidden to leave the house, except to walk up and down the drive within sight. They could find nothing to do except sit about and suspect one another.”

So there you are, if you find yourself sitting around on Christmas Day gazing at your loved ones and suspecting them of murder, it’s probably best to distract yourself with an intellectual pursuit or a long walk. Besides, I guarantee they almost definitely didn’t kill anyone.

(Images from Goodreads)

Secondly, Christmas Pudding by Nancy Mitford (1932, the lovely edition above is by Capuchin Classics, 2012), in which no murders take place despite a family being holed-up together in a country house for the season.

“’Oh what heavenly fun it will be!’ and Bobby vaulted over some fairly low railings and back, casting off for a moment his mask of elderly roué and slipping on that of a tiny-child-at-its-first-pantomime, another role greatly favoured by this unnatural boy.”

This being Mitford, the family and assorted hangers-on have names like Bobby Bobbin, Lord Leamington Spa, and my favourite, Squibby Almanack. Christmas Pudding is just such a joy – a silly, farcical, witty, clever, well-observed joy. There’s a plot of sorts: pretentious author Paul Fotheringay wangles his way into Compton Bobbin – “one of those houses which abound in every district of rural England, and whose chief characteristic is that they cannot but give rise, on first sight, to a feeling of depression in any sensitive observer” – under false pretences of being a tutor to the mercurial Bobby, and finds himself vying with Lord Lewes for the romantic attentions of Philadelphia Bobbin. But really, who cares? The fun of this novel isn’t in what happens, it’s in Mitford’s sharp observations “a woman had either a good reputation or an international reputation” and ridiculous characters interacting with one another.

“Bobby was now seldom to be seen; he spent most of his time giggling in corners with Miss Heloise Potts, a pretty black-eyed little creature of seventeen who substituted parrot-like shrieks and screams of laughter for the more usual amenities of conversation”

“’Squibby dear,’ said the duchess, waving an empty glass at Bobby as she spoke, ‘just tell me something. Have you seen Rosemary and Laetitia latishly? Are they alright, the sweet poppets?’”

I can’t help thinking it’s a shame that Lady Bobbin never met Lord Melbury, as she also tends to blame the Bolsheviks for anything she doesn’t like (in this instance foot-and-mouth disease which prevents her hunting). But if you think these references mean Mitford’s work is politically dated, let me give you this little nugget:

“He was evidently a man of almost brutish stupidity, and Paul, who had hardly ever met any Conservative Members of Parliament before, was astounded to think that such a person could be tolerated for a moment at the seat of government.”

Ahem.

I highly recommend this, in fact I’m almost tempted to say the thing that should never be said about humourous novels, but its Christmas and I’m drunk feeling festive so I’m going to say it anyway: if you like Wodehouse, I think you’ll like this 🙂

If this has whetted your appetite for golden age country house mysteries, the BBC is screening an adaptation of Agatha Christie’s classic And Then There Were None (which is admittedly an island house rather than a rural one) on Boxing Day:

Season’s Greetings to you all!