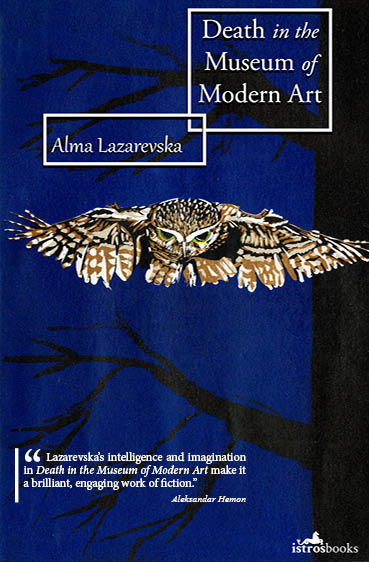

For this year’s Women in Translation Month I’m trying to focus on countries I’ve yet to visit on my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge. Today I’m off to Bosnia and Herzegovina via Death in the Museum of Modern Art by Alma Lazarevska (1996 transl. Celia Hawkesworth 2014) published by Istros Books.

Death in the Museum of Modern Art is a collection of six stories set during the siege of Sarajevo, although Lazarevska never names the “besieged city” that features in all the tales. Lazarevska is a Bosnian writer and survivor of the siege.

I always find it really hard to write about short story collections, so I’ll just focus on the opening and closing tales. In Dafna Pehfogl Crosses the Bridge between There and Here, the titular character reflects on her long. “unlucky”, “clumsy” life, starting when the maid burned the last coffee listening to her mother’s labour screams. Dafna is something of a scapegoat for her family and remained unmarried as her suitors weren’t smart enough for her family. Now in old age she finds herself alone in the war-torn city. Her family on “the other side” have arranged her passage to safety.

“She stepped boldly and decisively. Freed from other people’s gaze and lengthy sighs. Her feet were light on the deserted bridge between there and here.”

This is the only story in the collection written in the third person, but it didn’t distance Dafna in any way. I really hoped she’d make it to safety…

The final story, Death in the Museum of Modern Art has a dry humour to it. The narrator is answering questions that will form part of an exhibition at MoMA, including “How would you like to die?”

“I would have liked to tell him about that terrible feeling I have of being late… the feeling that I have being overtaken and I’m losing my sense of being present. Neither here, nor there.”

Without heavy judgement, Lazarevska demonstrates how the lived experience of war is being simplified and packaged up for art consumers. The impossibility of the questionnaires even beginning to capture anything meaningful from such a situation.

“But for an American, one ‘easy’ is the same as another. Hence a visitor to the Museum of Modern Art may read that my friend the writer wanted to die easily. He understands that, but the writer does not. That word introduces confusion into the writer’s answer. Can wishes of this kind be expressed in a foreign language, particularly one that does not distinguish one ‘easily’ from another?”

Lazarevska writes in a constrained style, both tonally and structurally. She doesn’t waste a word and has a real command of the short story form – I thought the six stories in this collection were all equally strong.

Lazarevska writes about the siege of Sarajevo in a way that is evocative but not overly emotive, trusting that the circumstances are extraordinary and shocking enough that they don’t need embellishment. Her focus is broadly domestic, looking at how ordinary lives find ways to carry on. The result is a compelling and memorable collection that places the reader alongside the characters as they hold onto their humanity through the most brutal experience.

“The hand I write with his healed. If any new questions should ever arrive, I shall write my answers myself. I’m writing all of this with my own hand.”