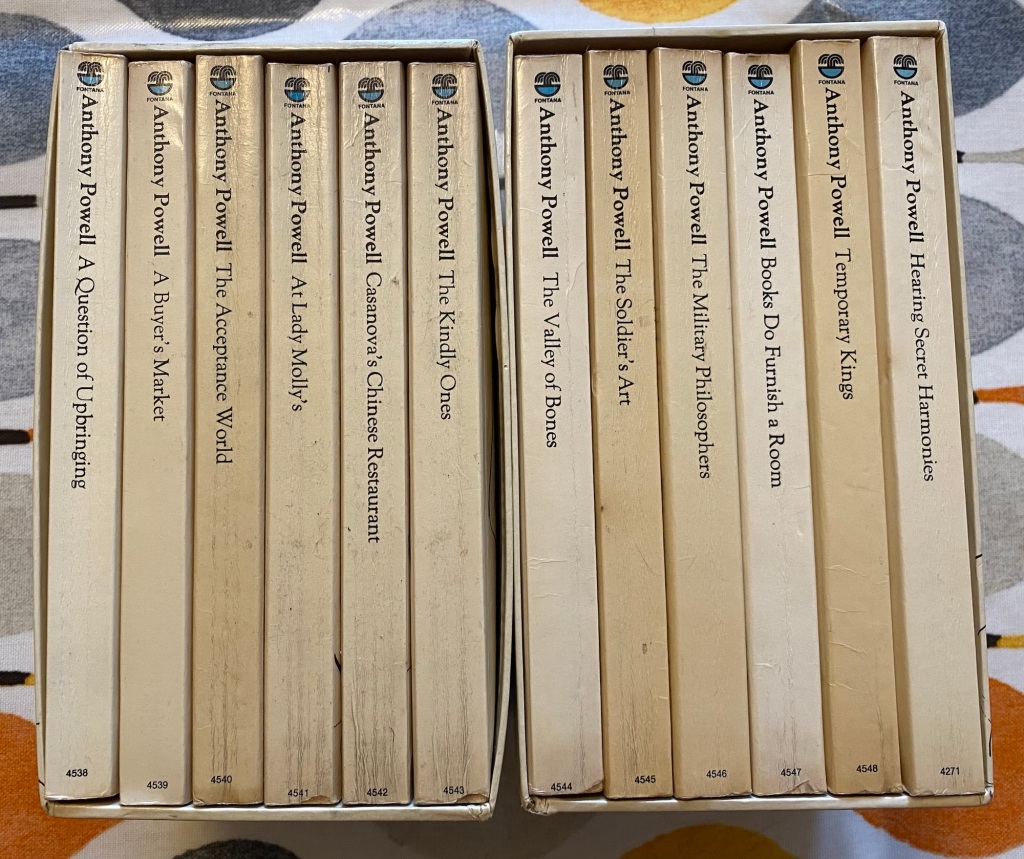

This is the eighth instalment in my 2024 resolution to read a book per month from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time sequence. Published between 1951 and 1975, and set from the early 1920s to the early 1970s, the sequence is narrated by Nicholas Jenkins, a man born into privilege and based on Powell himself.

The eighth volume, The Soldier’s Art, was published in 1966 and is set in 1941.Unlike the previous few novels, this only had three chapters, the middle one depicting Nick’s leave in London, bookended by his experiences in the army while still billeted in Northern Ireland.

As I mentioned in the previous volume’s post, Nick doesn’t really fit in with army life. But he doesn’t particularly labour on this, or feel sorry for himself. I enjoyed this exchange when he runs into Bithel again:

“’Told me you were a reader – like me – didn’t you?’

‘Yes I am. I read quite a lot.’

I no longer attempted to conceal the habit, with all its undesirable implications. At least admitting to it put one in a recognisably odd character of persons from whom less need be expected than the normal run.”

In this volume I felt I saw a much fuller picture of Nick’s touchstone Widmerpool. Is machinatious a word? If it isn’t, the character of Widmerpool suggests it should be, because his machinations inform his behaviour through and through.

Nick is acting as his secretary, desperate to get away.

“Indeed, it was often necessary to remind oneself that low spirits, disturbed moods, sense of persecution, were not necessarily the consequences of serving in the army, or being part of a nation at war, with which all inclusive framework depressive mental states now seemed automatically linked.”

Nick manages to stay out of Widmerpool’s connivances due to the latter’s egomaniacal need for control. However, he can observe his senior officer’s behaviour at much close quarters than before, including:

“An amateur soldier in relation to tactical possibilities, and … a professional trafficker in intrigue”

“[My] incredulity was due, I suppose, to an underestimation, even after the years I had known him, of Widmerpool’s inordinate, almost morbid self-esteem.”

By the end of the novel Widmerpool is moving on, and I had a horrible feeling that by the end of this novel sequence he might be Prime Minister…

Another of Nick’s schoolfriends is present in the company. Stringer, maintaining his sobriety, turns up as a mess waiter.

“Friendship, popularly represented as something simple and straightforward – in contrast with love – is perhaps no less complicated, requiring equally mysterious nourishment”

Stringer is an intriguing character, with a deep sense of sadness about him. We’ve never learnt what led him to self-medicate with alcohol, and now he is sober he seems to have an extreme resignation to life. He seems too equanimous, knowing no joy. I find him quite haunting.

In the middle chapter Nick uses his leave to visit friends in London. His wife Isobel and young child get a passing reference. If I was Isobel I’d be mightily annoyed that my husband spent his army leave in Blitz-torn London rather than in the country with his newly-expanded family, but maybe she’s more tolerant than I am.

This middle section was hugely moving. Powell conveys the tragedy of war, of lives cut short without warning. Of the senseless waste and cruel arbitrariness of it all. He does it all with understatement which perfectly drives home the horror, and how this became a regular occurrence for so many. It was an astonishing chapter.

It is in army life that Powell finds his comedy and satire. This was probably the most sad, most moving, and most silly and funny of all the volumes I’ve read so far.

I particularly enjoyed a completely daft dinner scene between two Colonels, one called Eric, one called Derrick. Powell uses the rhyming names to full effect, having both of them end their sentences with the other’s name, as they engage in a furious, but politely mannered argument.

“Both habitually showed anxiety to avoid a junior officer’s eye at meals in case speech might seem required. To make sure nothing so inadvertent should happen, each would uninterruptedly gaze into the other’s face across the table, with all the fixedness of a newly engaged couple, eternally enchanted by the charming in appearance of the other.”

There’s also Nick’s experience of inciting the wrath of a General, when he admits he doesn’t like Trollope and prefers another author:

“‘There’s always Balzac, sir.’

‘Balzac!’

General Liddament roared the name. It was impossible to know if Balzac had been a very good answer or a very bad one.”

The more I read of this sequence the more impressive I find it. Powell’s wit, humanity, clear-sightedness, and ability to balance the various aspects of life are really extraordinary. And he does it all with such a light touch.

“All the same, although the soldier might abnegate thought and action, it has never been suggested that he should abnegate grumbling.”

To end, I’m feeling quite smug for working out that I can shoehorn in an 80s pop video by choosing one by some of the Blitz Kids (and fair to say 80s pop videos did not generally follow an Anthony Powell-esque light touch 😀 ):