The 1954 Club is running all this week, hosted by Simon and Kaggsy. Do take a look at the posts and join in if you can, the Club weeks are always great events 😊

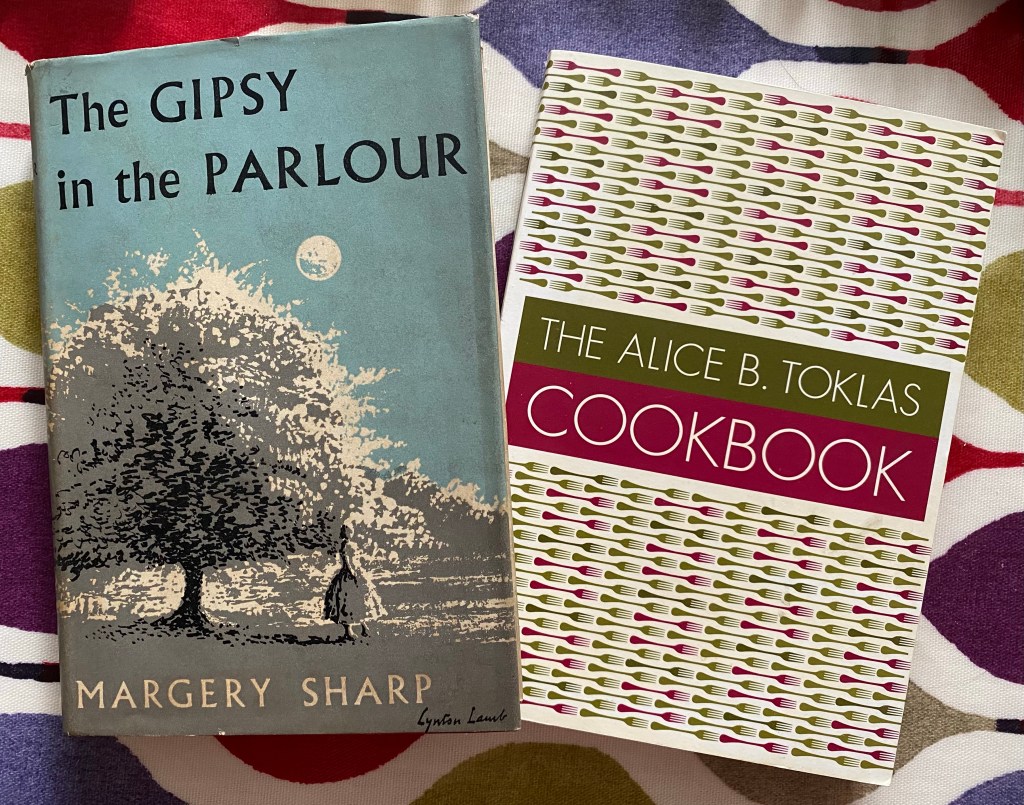

For this contribution, I thought I’d look at two books on a domestic theme. Firstly, The Gipsy in the Parlour by Margery Sharp. Despite the concerning title I can confirm while there is definitely dated language, it’s not prevalent throughout the novel.

The story is set in the 1870s and told from the point of view of an unnamed cousin of the family, looking back on her childhood as an adult now in the 1920s. This means Sharp manages a 11 year-old’s point of view without getting too caught by it, and it works well.

The child loves visiting her family in Devon, leaving behind the fog and grime of London for a West Country summer. She also leaves behind her cold, distant parents for her beloved aunts, Charlotte, Grace and Rachel. They have all married into the Sylvester family and form a capable team who run the domestic affairs of the farm with good-natured hard work.

“Nature had so cheerfully designed them that even wash-day left them fair-tempered: before the high festivity of a marriage their spirits rose, expanded and bloomed to a solar pitch of jollification.”

At the start of the novel they await the arrival of a fourth sister-in-law, who is going to marry Stephen Sylvester, the kindest of the male members of the family (who feature very little in the child’s world, due to their “effortlessly preserved complete inscrutability”). However, when Fanny Davis arrives, she is very different to the rest of the family – thin and pale rather than hale and hearty.

“She seemed to have nothing to say. She had neither opinions nor tastes. She hadn’t even an appetite. The amount she left on her plate would have fed a plough-boy – I believe often did feed a plough-boy”

The family know very little about Fanny “the most that could be discovered was a sort of shadow-novelette” but they welcome her in. However, it isn’t long before trouble strikes. Although Fanny attends a dance with family, whirling around quite happily, it isn’t long before she enters a Decline, and has to spend her days laying in the parlour.

The 11 year-old enlightens us:

“I knew a good deal about declines. A friend of my mother’s had a daughter who had been in one for years. Declines also occurred frequently in cook’s novelettes”

And

“No common person ever went into one. Common persons couldn’t afford to. Also, there needed to be a sofa. No sofa, no decline.”

As the narrator boldly plans to cure Fanny, in the manner of an Angel-Child in a novelette, the reader knows more is going on than the characters realise. Quite what Fanny is up to only gradually emerges, and in the meantime Sharp shows how destructive one person can be for previously happy family. Fanny may be persistently reclined but she is never passive, and she causes a great deal of stress and heartache for the Sylvesters.

Meanwhile, the narrator back in London is making a great friend of Clara Blow, the sort-of landlady to her handsome cousin Charlie. Despite Fanny’s frequent assurances to the young girl that they are “special friends”, it is loyalty to Clara that causes conflict for the narrator and makes her question what is actually happening back in Devon.

Will Fanny’s machinations come to light? Will the Sylvester family find a way back to happiness? Will everything work out in the end? Despite this being not as broadly comic as other Sharp novels I’ve read, I was never in any doubt that all would come right. Which it did 😊

Secondly, a slight departure, as I’m going to review a cookery book. Except it’s not really a review of the recipes in The Alice B Toklas Cookbook. There are plenty of recipes, but the book is a memoir too, which is what makes it all the more interesting. Alice B Toklas was the life-partner of Gertrude Stein, and as she reminisces about growing and eating food, she records their life together and meals taken with the many well-known artists who crossed their path, such as decorating a bass fish to entertain Picasso (we’ve all been there, desperately trying to create piscine entertainment for a Cubist in a Rose Period).

She also recalls living through France during the war: “In the beginning, like camels, we lived on our past.” They live through rationing: trading cigarettes with soldiers, and Gertrude Stein acquiring food on the black market through force of personality.

“When in 1916 Gertrude Stein commenced driving Aunt Pauline for the American Fund for the French Wounded, she was a responsible if not an experienced driver. She knew how to do everything but go in reverse.”

Aunt Pauline is their Model T Ford, succeeded by Godiva:

“Even though Godiva was what a friend ironically called a gentleman’s car, she took us into the woods and fields as Auntie had. We gathered the early wildflowers, violets at Versailles, daffodils at Fontainebleau, hyacinths (the bluebells of Scotland) in the forest of Saint Germain. For these excursions there were two picnic lunches I used to prepare.”

But just in case this excursion sounds too idyllic…

“Back in Godiva on the road again it was obvious that somewhere we had made a wrong turning. Was Godiva or Gertrude Stein at fault? In the discussion that followed we came to no conclusion.”

One of my favourite stories was of Alice making raspberry flummery for a friend in the resistance who has a sweet tooth. It leads to a conversation about gelatine, the friend borrowing several sheets. Alice later finds out this is because it is essential for making false papers.

This is not the book to read if you want some easy, quick recipes to cook after work (and of course Alice and Gertrude had domestic staff to help them, several described in the book). There is more than one recipe that calls for 100 frogs legs, but as Maureen Duffy points out in her introduction, is that the legs of 100 frogs, or 100 legs in total? There’s also the detailing of how to prepare a leg of mutton by injecting it with orange juice and brandy for a week.

In case it’s not already apparent, this is also not the book to support a plant-based diet. Toklas acknowledges this, naming Chapter 4 “Murder in the Kitchen”. A vast quantity of eggs seem necessary to many recipes. When I came across a recipe for frangipane tart I thought I’d finally found something I’d enjoy, but it was like no frangipane I’d ever encountered. However, Chapter 5 Beautiful Soup, was quite tempting with its descriptions of various ways to make gazpacho.

I didn’t know this before I read the book, but the interwebs tell me that the recipe for haschich fudge is the most famous. Apparently the first publisher didn’t realise what it was and so allowed it to be printed, perhaps misled by Alice’s mischievous suggestion that “it might provide an entertaining refreshment for Ladies Bridge Club or a chapter of the DAR”.

My favourite chapter was 13, “The Vegetable Gardens at Bilignin”. Alice’s passion for the garden shone through:

“For fourteen successive years the gardens at Bilignin were my joy, working in them during the summers and planning and dreaming of them during the winters”

Her descriptions of the gardens and produce were absolutely lovely:

“The day the huge baskets were packed was my proudest in all the year. The cold sun would shine on the orange-coloured carrots, the green, the yellow and white pumpkins and squash, the purple eggplants and a few last red tomatoes. They made for me a more poignant colour than any post-Impressionist picture.”

Again, the love of Alice’s life undercuts the romanticism:

“Gertrude Stein took a more practical attitude. She came out into the denuded wet cold garden and, looking at the number of baskets and crates, asked if they were all being sent to Paris, that if they were the expressage would ruin us.”

There are a million quotable and notable passages in this cookbook. If you’ve any interest in Stein and Toklas, in interwar France, or in generation perdu, I’d urge you to get this. You can just dip into it and there’s always something to entertain, but probably not much to cook…

“From Madame Bourgeois I learned much of what great French cooking was and had been but because she was a genius in her way, I did not learn from her any one single dish. The inspiration of genius is neither learned nor taught.”

To end, Dorothy Dandridge in an Oscar-nominated performance in 1954’s Carmen Jones: