I had such a book hangover after Bleak House. I couldn’t settle to anything. A friend of mine who loves a certain 80s singer has a phrase when she hears other warblers: “He’s alright, but he’s not George Michael.” Well, I kept picking up books that were alright, but they weren’t Bleak House. So few books are, I find…

Then I remembered that when Simon did his books of the year round up last year, I’d recognised two were on my TBR pile. Surely books good enough to make the final cut would see me right? Of course they did 😊 Hooray for bloggers and their brilliant recommendations!

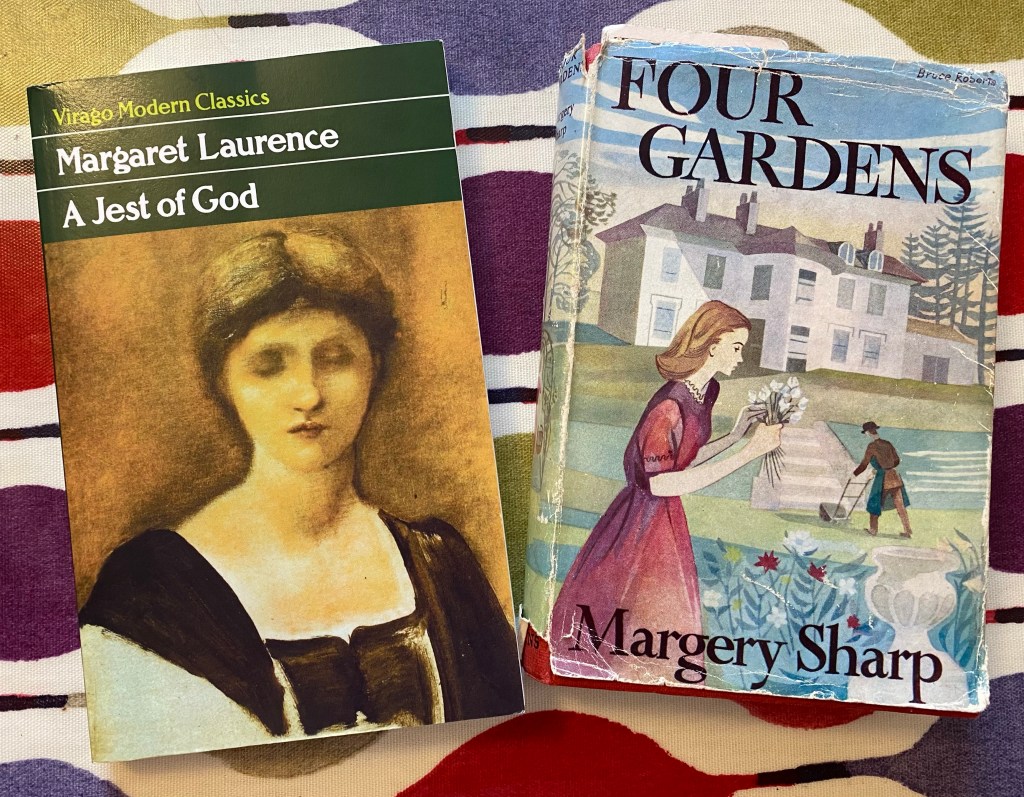

Firstly, the novella which made the top of Simon’s list, A Jest of God by Margaret Laurence (1966). This was the second in Laurence’s Manawaka sequence, but thankfully they can all be read as standalones as I’d not read anything by her before. On the strength of this, I’ll definitely be seeking out her writing again.

A Jest of God is an intimate character study of Rachel Cameron, a thirty-four-year-old teacher who lives with her emotionally manipulative mother above the Manitoba funeral business her father ran until he died.

The novel is narrated in the first-person, and Rachel’s mind is an oppressive and tense place to be. She is highly anxious and self-censoring:

“There. I’m doing it again. This must stop. It isn’t good for me. Whenever I find myself thinking in a brooding way, I must simply turn it off and think of something else. God forbid that I should turn into an eccentric. This isn’t just imagination. I’ve seen it happen. Not only teachers, of course, and not only women who haven’t married. Widows can become extremely odd as well, but at least they have the excuse of grief.”

This anxiety and second-guessing is not helped by her mother’s behaviour, which is self-pitying, judgemental and highly manipulative. Rachel recognises this, but is at a loss as to how to extricate herself:

“Her weapons are invisible, and she would never admit even to carrying them, much less putting them to use.”

“All such words cling to the mind like burrs to hair, and I can never seem to brush them away, as I know I should do.”

Rachel’s mother is not an out-and-out baddie though, and Laurence expertly demonstrates the vulnerability and fear that underlies her machinations. Similarly, Rachel does not always behave well. In one particular scene early in the book, she actually behaves despicably and doesn’t make amends despite her instant remorse. She is a complex, contradictory character, wholly believable. Laurence treats her tenderly but unflinchingly; without judgement but also without sentiment.

Rachel could so easily be a stereotype: a lonely single woman, living with her mother. But Laurence side-steps clumsy characterisation, or easy dismissal of Rachel, by delicately exploring the true meaning of the adjective so often attached to unmarried women approaching middle-age: she is desperate. She is absolutely desperate and despairing. She is lonely, and feels trapped in the life she has always known, with no way out. She wants things to be different, but she doesn’t know how. She is deeply, existentially sad.

1966 is a time of societal change, when women like Rachel could feel stifled by convention and also have some sexual freedom. So when Nick, and old schoolfriend appears, there are brief moments of physical connection. But in only seeing things from Rachel’s point view, the reader is able to realise how little intimacy there is. And that is what Rachel needs, more than the sex which Nick offers. Yet she doesn’t know how to achieve this:

“I talk to him, when he is not here, and tell him everything I can think of, everything that has ever happened, and how I feel and for a while it seems to me that I am completely known to him, and then I remember I’ve only talked to him like that when I’m alone. He hasn’t heard and doesn’t know.”

In some of Nick’s reported speech, the reader picks up on things Rachel ignores. She is so bound in her own intense feelings, she can’t really hear the cues Nick gives, over her relentless inner voice.

“He’s thirty-five, not fifteen. His past such gauche public performances. What he worried about Rachel? I’m not worried. I’m perfectly alright. Well, relax, then. I am relaxed. Oh? Shut up. Just shut up.”

A Jest of God is such an accomplished novel that is also so approachable. I found Rachel’s voice got under my skin very quickly and distinctly, and I had to read on. I think it works very well as short novel, longer would have been too oppressive and difficult to sustain I suspect. But at the length it is it remains powerful and impactful, and not as depressing as I’ve made it sound!

Ultimately there is resilience and change for Rachel, even some defiance. And there are brief moments of humour, such as Rachel trying to duck her colleague Calla’s constant invitation to attend Tabernacle with her:

“At least I have postponed it, and perhaps by that time some reasonable excuse will come along, or I’ll be dead.”

A stunning novel: a precise and compassionate character study, clever and humane. I’m so glad to have discovered Margaret Laurence at long last.

“Something must be the matter with my way of viewing things. I have no middle view. Either I fixed on a detail and see it as though it were magnified – a leaf with all its veins perceived, the fine hairs on the back of a man’s hands – or else the world recedes and becomes blurred, artificial, indefinite, an abstract painting of a world.”

Secondly, after being in Rachel’s head, I looked forward to some comic relief from an author I always enjoy: Margery Sharp. Four Gardens (1935) was number ten in Simon’s list. But this wasn’t as comic as some of her other novels; it had a slightly elegiac tone and the relationships included a certain sadness. But it wasn’t a sad novel overall, and I sunk into Four Gardens with pleasure.

Four Gardens follows the life of Caroline Chase from late teens to middle-age and the titular spaces she finds herself in. The device with gardens isn’t remotely heavy-handed and for a significant section of the novel they barely feature. But Caroline is a gardener, given half a chance, and it is instinctive and natural to her:

“Her step, as she now redescended to the rose garden, was therefore a proper gardeners tread – slow, considerate, with long abstracted pauses for survey and meditation. She also, without thinking, removed her hat and gloves.”

This is her first garden, one she trespasses into, and as she meets her first love there, it has a dreamlike quality. Perhaps this is why her love of gardening is so easily disregarded when she leaves behind youthful folly to marry the determinedly sensible Henry:

“For all these things in themselves – love at first sight, undying devotion, and general aloofness – were very exciting indeed; it was only in connection with Henry that they became so curiously prosaic.”

And so for many years Caroline doesn’t garden at all. She runs a house and she raises her son and daughter in the town where she has always lived. She is the creator of a safe space for her children and an unwavering routine for her staid but affectionate husband.

Despite the love she feels for her family and the tranquillity of her home life, I did find an element of melancholy to Caroline’s domestic arrangements. Her family are near and dear, but there seemed to be very little intimacy: she and Henry rarely communicate about anything beyond practical considerations, and she doesn’t really understand her children at all. She also despises her closest friend in the village, Ellen Watts – a monstrous and wholly believable creation. Caroline reflects very little though, and so any concerns are quickly subsumed in the relentless demands of domesticity:

“Thinking – the deliberate exercise of the brain – did not come naturally to her.”

But I wouldn’t want to give the impression that Four Gardens is ponderous or heavy-going in any way. It felt quite a realistic presentation of Edwardian contentment, though not without Sharp’s gentle jibes, such as this discussion of wallpaper where Caroline evokes her husband’s approval to counteract her mother’s reservations:

“Mrs Chase was at once silenced. […] It would have seemed perfectly reasonable to her that Caroline, who was in the house all day, should have suited her surroundings to the taste of a man who was out of it.”

I did want Caroline to exert herself in some way, to stake a claim beyond her roles meeting everyone else’s needs. Finally she does it, when she starts growing runner beans during World War I, and realises how much she is nurtured by time with her plants:

“there was usually a quiet space, between twelve and half-past, when the first work of the house was finished and before the children’s dinner became a pressing consideration; and these thirty minutes Caroline began to guard and cherish as a precious treasure.”

The war years are beautifully evoked by Sharp, with all their worry alongside self-serving censorious behaviour of some in the village. After the war, everything changes. Caroline finds herself mistress of a large house, with a garden she can’t touch unless she wants to incur the wrath of a succession of gardeners:

“The garden was looking well. But it always did look well, and gave her no special pleasure […] It was perfectly designed and perfectly kept, and to Caroline completely uninteresting.”

Meanwhile, her children are vaguely affectionate, patronising strangers. They change the names she loves, Lily becoming Lall and Leonard, Leon. They are academically accomplished and having had money their whole lives, utterly contemptuous of it. These Bright Young Things live by a morality that is absolutely baffling to Caroline, and there is a lovely echo of an earlier scene between Caroline and her mother in a later conversation between Caroline and Lall. The reader can see they are so much more alike than either realises, dramatic irony at its lightest.

I’m not one for biographical readings of novels but something of the tone of Four Gardens – affectionate, gentle, slightly sad – did make me consider the dates. In Caroline, Sharp is writing about her parents’ generation, so maybe that explains it… or maybe it has nothing to do with it at all, who knows?

Caroline’s fourth garden finally sees her able to do as she pleases. I couldn’t help feeling she might really surprise her children, and herself 😊 A warm, engaging story of a woman’s outwardly ordinary adult life during great societal change.

To end, Paul Newman adapted A Jest of God as Rachel, Rachel for his directorial debut. This very odd trailer doesn’t make it seem overly appealing:

I do like the sound of both of these. I’ve only recently started reading Sharp, and this looks like one worth exploring even if it does have that touch of melancholy. Laurence is new to me, but it would be interesting to enter the mind of one in Rachel’s situation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really like Sharp, I’ve yet to read one of hers I didn’t enjoy! I think you’d like this Mallika.

Laurence was new to me too. A Jest of God is so powerful, she really takes you inside Rachel’s mind. I definitely want to explore her writing further.

Hope you enjoy these if you get to them – I’d be really interested to hear your thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let me see if I can find copies

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fingers crossed! Dean Street Press have reprinted Four Gardens, and there’s an ebook too: https://www.deanstreetpress.co.uk/pages/book_page/384

LikeLike

Oh hurrah for dsp!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! 🙂

LikeLike

I totally get the book hangover thing – Dickens has been having that effect on me. A good way to recover is total contrast and sounds like these were brilliant choices. Laurence sounds great.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to know I’m not alone Kaggsy! They were great choices, I got there in the end 🙂 The Laurence was so powerful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pleased to hear these two cured you of your book hangover. Very much like the sound of both of them, best read in the order you chose!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, although I didn’t plan it the order was perfect! Glad you like the sound of them Susan 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my. I recognized my mother when I read this quotation “Her weapons are invisible, and she would never admit even to carrying them, much less putting them to use.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s so well observed Jeanne. The people were so recognisable which is what made it such a difficult read in places.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you managed to get back into enjoying reading. I agree, hooray for bloggers’ recommendations, including yours!

I read both of these books following Simon’s round up of 2022 post. I admired the evocative, intense writing in A Jest of God, but I really did not like it. I am sure it was me rather than the book and maybe just the wrong time but I found it too sad and intense in a bleak way.

I did enjoy Four Gardens. I think it is one of my favourite Sharp novels to date.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to hear Simon’s post prompted you to pick these up too!

I think a different ending would have meant I found AJOG bleak, but as it was I thought there was hope. I totally see what you mean though, it does have so much intense sadness in it.

I have about half of Sharp’s adult books left to read, and I’m sure Four Gardens is one that will stay with me 🙂

LikeLike

Anything that includes the beautiful Paul Newman is alright by me…even an odd trailer!

LikeLiked by 1 person

He really was so beautiful… sigh…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Urgh. Nothing worse than a book hangover. I usually change genres when this happens. Or formats (which is generally when I break out an audiobook). But some books are such that everything pales against it – glad you found your way back 🙂

PS. I tend to agree with your friend re George 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those are good tips Kate! I’m very relieved the hangover is finally banished.

I absolutely agree with her too 🙂

LikeLike

I have read three of the Manawaka sequence by Margaret Laurence. I read in the wrong order but don’t think it mattered. The Jest of God was my favourite of the three, although they were all brilliant. I really engaged with Rachel as a character.

I will have to put Sharp’s Four Gardens on my list, it sounds great.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really good to know Ali, I definitely want to read more by Laurence, I thought AJOG was so powerful.

I think you’d really like Four Gardens – I hope so! An understated, well-observed story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lovely reminder that I really need to read some more Margery Sharp as she seems right up my street! I’ve only read a couple of her stories so far – both excellent – so it’s probably time to get into her novels. You’ve mentioned that Four Gardens isn’t as humorous as some of Sharp’s other novels. Nevertheless, the elegiac tone appeals…Where would you suggest I start properly with her?

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you’re tempted by Margery Sharp Jacqui! The Eye of Love was the first I read by her and it retains a special place in my heart for that reason – the determinedly individual child Martha and her relationships with the two adults is just lovely. But probably the place to start is Cluny Brown – I think this is likely the most popular of her novels and introduces readers to Sharp’s humour and her recurring motif of a central female character being gently at odds with her surroundings! I really hope you enjoy her, I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts.

LikeLike

Brilliant. Thanks so much for this, very helpful indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bleak House is brilliant and these two books both sound great, but Rachel Rachel? I’m aghast!! And Paul Newman talking about the mystery of women, oh please. . . !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like the sound of these Jane!

I mean, maybe Rachel Rachel is a really great film and they just made a terrible trailer?! 😀 But I share your reaction!

LikeLiked by 1 person