I first heard about Brandy Sour by Constantia Soteriou (2022, transl. Lina Protopara 2024) on Winston’s Dad’s blog – I thought quite recently but I can see it was August 2024! I get there eventually…

This is a contribution to the marvellous #ReadIndies event hosted by Kaggsy, and it also means Cyprus is the next stop on my Around the World in 80 Books reading challenge (3 stops to go!)

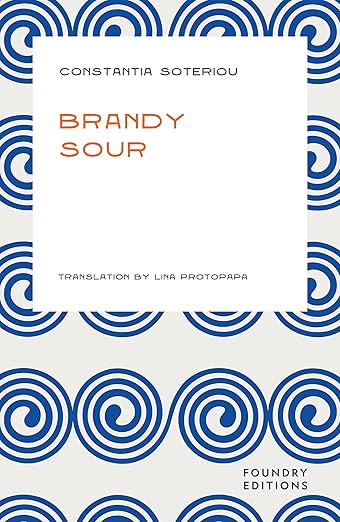

Brandy Sour published by Foundry Editions, an independent publisher focussed on Mediterranean authors who are new to Anglophone readers. I love their styling, where their (French flap!) covers are “designed to capture the visual heritage of the Mediterranean”. This one is based on a third century BCE Hellenic vessel.

This short novella builds the stories of a cast of characters around two central constructs: their relationship to the Ledra Palace Hotel, and the drinks they have (with one colourful exception – I was relieved the chapter’s titular fluid was not imbibed!) The 22 vignettes work brilliantly, as Soteriou charts the history of Cyprus in the latter part of the twentieth century with the lightest of touches.

It begins with the bartender who takes the recipe for the titular drink to the new hotel, having first made it for King Farouk of Egypt:

“It’s a Cypriot drink, with ingredients from our island, that you serve in a tall glass after you sugar its rim, a drink full of cognac and lemonade that seems and tastes innocent but is not. It’s a drink worthy of kings who want to deceive people, a drink that isn’t what it seems to be, that looks like iced tea and that you can drink publicly without anyone knowing what it contains. It’s a drink full of secrets — that’s why it was made here.”

We meet the staff of the hotel and the guests, as it offers luxury and glamour through the 1950s and 1960s, from colonialism to independence. But as we know from ‘The Guerilla Fighter’ and his VSOP brandy straight from the bottle, discontent is brewing.

When the coup occurs ‘The Turk’ can no longer move freely past the hotel and the street vendor for his salted yogurt drink:

“The last time he attempts to walk past the big hotel, they stop him and tell him he needs to go back. He needs to find another way to work, another way to get his ayran; or maybe he needs to stop drinking it altogether—or find another place to buy it from. In a matter of days, everything will change.”

The upheaval of the war is evoked dramatically but not sensationally, through the individuals. The hotel is the site of a terrible battle, and the chapter ‘Water: The Mother’ demonstrates this with direct, effective simplicity.

The hotel ends up in the UN buffer zone, housing officials and falling to ruin.

But Soteriou also weaves in the flora of Cyprus, showing the natural beauty of the island. There is the lavender tea beloved of the architect of the hotel; jasmine tea drunk by ‘The Poet’ guest; elderflower used by ‘The Fiancee’ who bathes her eyes after her betrothed – and dreams of a wedding in the hotel – are snatched during the coup. The two mayors of the split city of Nicosia try and find common ground over spearmint tea, an old lady reminisces about Seville orange liqueur which she made and sold as a young woman.

My favourite of these was the melancholy ‘Doorman’ and his rosebud tea.

“You can have your rose tea hot or iced, you can have it in the winter and in the summer too, and it’s also good for your stomach, it helps digest the indigestible. It’s a little sweet and a little spicy – it reminds you of the village and of your mother.”

He sneaks the hundred petal Cypriot damask rose into the English rose garden in the grounds and plants it there. Later the garden is razed to build a pool, bar and tennis courts. He manages to save a few roses, but the infusion is bitter.

In just 104 pages I thought Brandy Sour was a brilliant achievement. Ambitious but never weighed down by its ambition; exploring seismic events without losing sight of the human cost; both sad and funny and always intensely readable. It consistently demonstrates the importance of small rituals shared by ordinary people as moments of resistance and resilience.

And now my TBR will spiral as I explore Foundry Editions further… 😀